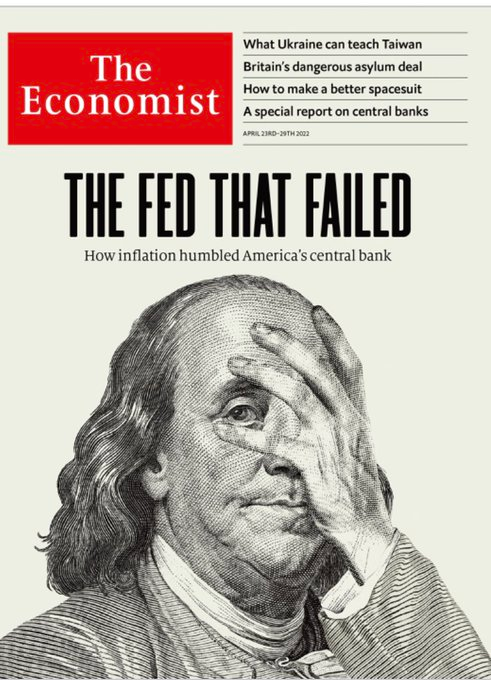

Come abbiamo scritto in più e più occasioni, la Federal Reserve è passata nello spazio di soli due anni da una situazione di (apparente) onnipotenza, ovvero dal potere agire senza alcun limite e al di fuori di qualsiasi controllo, ad una situazione di pressoché totale impotenza, una situazione nella quale la Fed non ha più spazi di manovra e può fare soltanto più ciò che è COSTRETTA a fare.

Costretta da qualcuno? No. E’ costretta dalla realtà. Dalla realtà dei fatti, che intorno a lei, intorno alla Fed, si è trasformata con una tale rapidità che prima la Fed non è riuscita a capire, a comprendere, e poi non è riuscita a seguire.

Per questo, adesso, è costretta: è costretta a rincorrere, può solo rincorrere, ha una sola strada davanti da percorrere.

Oggi, quelli che sono stati (per pochi mesi) gli Onnipotenti vengono trascinati al laccio, come animali da bestiame.

Le scelte che la Fed oggi può fare, e che inevitabilmente farà, sono solo quelle del linguaggio: scelte che hanno ed avranno pochissimo impatto sulla realtà, in futuro, ma che potrebbero averne uno (anche molto grande) sulla psicologia del pubblico, e degli investitori in particolare nell’immediato. Lo abbiamo già messo in evidenza in un Post di sabato 30 aprile qui nel Blog.

Le scelte di linguaggio della Federal Reserve, dopodomani, potrebbero muovere i mercati finanziari: anche se soltanto nel brevissimo termine.

A nostro avviso, molto dipenderà dal tipo di scenario, dal tipo di prospettiva di medio termine che verrà scelta dal Consiglio della Federal Reserve per presentare le proprie scelte in materia di tassi ufficiali di interesse e di riduzione dell’attivo.

Per questa ragione, noi suggeriamo ai nostri lettori di leggere con attenzione l’articolo che noi abbiamo selezionato e che alleghiamo qui per intero.

Vi suggeriamo non soltanto di leggere questo articolo, ma pure di prendere nota con carta e penna dei temi che in questo articolo vengono toccati: si tratta solo in apparenza di tematiche lontane che resto sullo sfondo delle decisioni di investimento.

Al contrario, noi crediamo che mercoledì saranno proprio questi temi a segnare la reazione dei mercati: la Federal Reserve sicuramente li prenderà in esame, e (noi crediamo) li utilizzerà poi per comunicare. la Fed li utilizzerà come “paletti” per delimitare un perimetro, per comunicare al pubblico “noi alziamo il costo del denaro, ma lo facciamo all’interno di un perimetro ben delimitato, per questa e quest’altra ragione”.

Lo scopo? Allontanare dalla mente dell’investitore i dubbi sulla consapevolezza della stessa Fed in questa fase.

Ed in particolare, allontanare il dubbio che gli uomini della Fed abbiamo, molto semplicemente, perso il controllo delle cose.

Passando così da Onnipotenti a Ostaggi della situazione.

While recent shocks have made the current inflationary surge and growth slowdown more acute, they are hardly the global economy’s only problems. Even without them, the medium-term outlook would be darkening, owing to a broad range of economic, political, environmental, and demographic trends.

The new reality with which many advanced economies and emerging markets must reckon is higher inflation and slowing economic growth. And a big reason for the current bout of stagflation is a series of negative aggregate supply shocks that have curtailed production and increased costs.

This should come as no surprise. The COVID-19 pandemic forced many sectors to lock down, disrupted global supply chains, and produced an apparently persistent reduction in labor supply, especially in the United States. Then came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has driven up the price of energy, industrial metals, food, and fertilizers. And now, China has ordered draconian COVID-19 lockdowns in major economic hubs such as Shanghai, causing additional supply-chain disruptions and transport bottlenecks.

But even without these important short-term factors, the medium-term outlook would be darkening.

There are many reasons to worry that today’s stagflationary conditions will continue to characterize the global economy, producing higher inflation, lower growth, and possibly recessions in many economies.

For starters, since the global financial crisis, there has been a retreat from globalization and a return to various forms of protectionism. This reflects geopolitical factors and domestic political motivations in countries where large cohorts of the population feel “left behind.” Rising geopolitical tensions and the supply-chain trauma left by the pandemic are likely to lead to more reshoring of manufacturing from China and emerging markets to advanced economies – or at least near-shoring (or “friend-shoring”) to clusters of politically allied countries. Either way, production will be misallocated to higher-cost regions and countries.

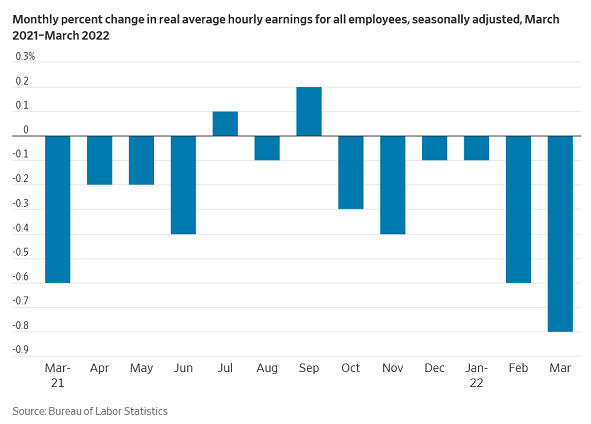

Moreover, demographic aging in advanced economies and some key emerging markets (such as China, Russia, and South Korea) will continue to reduce the supply of labor, causing wage inflation. And because the elderly tend to spend savings without working, the growth of this cohort will add to inflationary pressures while reducing the economy’s growth potential.

The sustained political and economic backlash against immigration in advanced economies will likewise reduce labor supply and apply upward pressure on wages. For decades, large-scale immigration kept a lid on wage growth in advanced economies. But those days appear to be over.

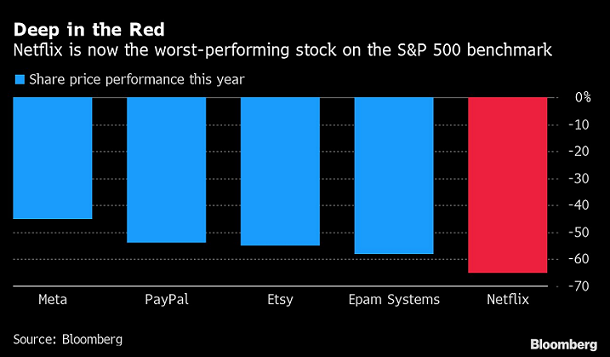

Similarly, the new cold war between the US and China will produce wide-ranging stagflationary effects. Sino-American decoupling implies fragmentation of the global economy, balkanization of supply chains, and tighter restrictions on trade in technology, data, and information – key elements of future trade patterns.

Climate change, too, will be stagflationary. After all, droughts damage crops, ruin harvests, and drive up food prices, just as hurricanes, floods, and rising sea levels destroy capital stocks and disrupt economic activity. Making matters worse, the politics of bashing fossil fuels and demanding aggressive decarbonization has led to underinvestment in carbon-based capacity before renewable energy sources have reached a scale sufficient to compensate for a reduced supply of hydrocarbons. Under these conditions, sharp energy-price spikes are inevitable. And as the price of energy rises, “greenflation” will hit prices for the raw materials used in solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and other clean technologies.

Public health is likely to be another factor. Little has been done to avert the next contagious-disease outbreak, and we already know that pandemics disrupt global supply chains and incite protectionist policies as countries rush to hoard critical supplies such as food, pharmaceutical products, and personal protective equipment.

We must also worry about cyberwarfare, which can cause severe disruptions in production, as recent attacks on pipelines and meat processors have shown. Such incidents are expected to become more frequent and severe over time. If firms and governments want to protect themselves, they will need to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on cybersecurity, adding to the costs that will be passed on to consumers.

These factors will add fuel to the political backlash against stark income and wealth inequalities, leading to more fiscal spending to support workers, the unemployed, vulnerable minorities, and the “left behind.” Efforts to boost labor’s income share relative to capital, however well-intentioned, imply more labor strife and a spiral of wage-price inflation.

Then there is Russia’s war on Ukraine, which signals the return of zero-sum great-power politics. For the first time in many decades, we must account for the risk of large-scale military conflicts disrupting global trade and production. Moreover, the sanctions used to deter and punish state aggression are themselves stagflationary. Today, it is Russia against Ukraine and the West. Tomorrow, it could be Iran going nuclear, North Korea engaging in more nuclear brinkmanship, or China attempting to seize Taiwan. Any one of these scenarios could lead to a hot war with the US.

Finally, the weaponization of the US dollar – a central instrument in the enforcement of sanctions – is also stagflationary. Not only does it create severe friction in international trade in goods, services, commodities, and capital; it encourages US rivals to diversify their foreign-exchange reserves away from dollar-denominated assets. Over time, that process could sharply weaken the dollar (thus making US imports more costly and feeding inflation) and lead to the creation of regional monetary systems, further balkanizing global trade and finance.

Optimists may argue that we can still rely on technological innovation to exert disinflationary pressures over time. That may be true, but the technology factor is far outnumbered by the 11 stagflationary factors listed above. Moreover, the impact of technological change on aggregate productivity growth remains unclear in the data, and the Sino-Western decoupling will restrict the adoption of better or cheaper technologies globally, thereby increasing costs. (For example, a Western 5G system is currently much more expensive than one from Huawei.)

In any case, artificial intelligence, automation, and robotics are not an unalloyed good. If they improve to the point where they can create meaningful disinflation, they also would probably disrupt entire occupations and industries, widening already large wealth and income disparities. That would invite an even more powerful political backlash than the one we have already seen – with all the stagflationary policy consequences that are likely to result.