La Federal Reserve del 4 maggio 2022: l'inflazione 2021 - 2022 - 2023

Come tutti i lettori del Blog sanno, Recce’d ha smesso di scrivere di Federal Reserve un anno e mezzo fa: in questo ultimo anno e mezzo, sarebbe stato inutile.

Questo perché la Federal Reserve, dalla seconda metà del 2020, per tutto il 2021, e in questo inizio di 2022, è rimasta non soltanto senza parole, ma pure senza strumenti, senza leve, senza armi, senza spazio di manovra. (E la BCE sta messa ancora peggio, e di molto).

E quindi, nell’ultimo anno e mezzo, la Federal Reserve non è mai stata protagonista: ha semplicemente fatto ciò che era costretta a fare, data la situazione (assurda, ai limiti del folle) che lei stessa, la Banca Centrale, aveva contribuito a creare.

Recce’d tutto ciò che aveva da dire in proposito lo aveva chiarito nella parte finale del 2020. E prima ancora, nell’agosto 2020.

E ancora molto tempo prima, pensate: nel 2015.

Oggi, quello che Recce’d scriveva anni fa lo trovate sulla prima pagina dei più autorevoli quotidiani e periodici.

Perché allora, proprio oggi, Recce’d torna a scrivere ai suoi lettori della Federal Reserve?

La ragione è molto semplice: perché adesso la Federal Reserve ritorna a contare. Non tanto sul piano pratico, dove le scelte della Federal Reserve potranno incidere ben poco.

Bensì sul piano della psicologia collettiva. Saranno le parole, più che gli atti, della Federal Reserve, ad incidere.

Dopo avere fatto una drammatica (ed ennesima) “svolta ad U” smentendo sé stessa poche settimane fa, quando ha riconosciuto che l’idea stessa di una “inflazione transitoria” era stata una tragica sciocchezza, adesso la Federal Reserve deve scegliere se continuare a mentire oppure se rispondere con chiarezza, concretezza e in modo esplicito alle domande che con sempre maggiore insistenza i mercati finanziari ed il pubblico dei risparmiatori e consumatori le rivolgono.

Le domande sono molte: anzi, sono decisamente troppe. la scelta della BCE e della Federal Reserve di fare per un anno e mezzo la parte del “pesce in barile” ha prodotto questo accumularsi di domande che ad oggi non anno una risposta.

Tra queste, una delle più importanti ed attuali è la seguente: “Quali sono le cause dell’inflazione 2021-2022?”.

Nell’articolo del Wall Street Journal che grazie a Recce’d avete la possibilità di leggere nella versione integrale qui di seguito viene presa una posizione forte: l’articolo è un editoriale firmato dal Board, dal Consiglio direttivo del quotidiano. Quindi, l’articolo esprime la “linea ufficiale” del maggiore quotidiani finanziario degli Stati Uniti.

Nell’articolo viene contesta la “versione ufficiale” oggi dominante, la “narrativa” che si vorrebbe imporre al pubblico: la storia che ci dice che la principale causa dell’inflazione è Putin.

E’ anche troppo facile smontare questa recente e nuova “narrativa”: sarà più che sufficiente rivedere i numeri per l’inflazione, negli Stati uniti ed in Europa, nei mesi di dicembre 2021 e di gennaio 2022. Ed il discorso è già chiuso.

Il Wall Street Journal pubblicava questo articolo una decina di giorni fa, a commento del più recente dato USA per l’inflazione nella versione CPI, che aveva fatto scrivere a molti di “peak inflation”, ovvero che negli Stati Uniti l’inflazione aveva toccato proprio con quel dato (riferito al mese di marzo 2022) il suo punto più alto.

Poi proprio ieri, venerdì 29 aprile, a smentire questa ipotesi di “peak inflation” è arrivato il dato per l’inflazione USA nella versione PCE, che nella seduta di quello stesso venerdì 29 aprile ha destabilizzato tutti i comparti del mercato finanziario.

Aggungete a questo dato il dato per l’inflazione tedesca, e per l’inflazione UE, che abbiamo letto sempre il 29 aprile, ed il quadro è completo ed esaustivo.

La lettura attenta di questo articolo, pertanto, è un contributo utilissimo per dare una risposta alla domanda: “Dove andrà l’inflazione nei prossimi mesi?”. Sia negli USA sia nell’Unione Europea. Una domanda alla quale nessun investitore può sottrarsi.

In aggiunta, vi aiuterà a riflettere sulle ricadute dell’inflazione sulla futura evoluzione della politica, sia negli Stati Uniti sia in Europa.

White House aides were out in force on Monday warning that Tuesday’s inflation report would be ugly and blaming it on Vladimir Putin. No doubt that beats blaming your own policies. But inflation didn’t wait to appear until the Ukraine invasion, and by now it will be hard to reduce.

The White House was right about the consumer-price index, which rose 1.2% in March, the highest monthly rise since the current inflation set in. The price rise in the last 12 months hit 8.5%, the fastest rate in 40 years.

Energy prices in the month contributed heavily to the increase, and some of that owes to the ructions in oil markets since the invasion. But so-called core prices, excluding food and energy, rose 6.5% over the last 12 months. Service prices excluding energy, which weren’t supposed to be affected by supply-chain disruptions, were up 0.6% for the month and 4.7% over 12 months.

The nearby chart shows that the inflation trend began in earnest a year ago at the onset of the Biden Presidency. It has accelerated for most of the last 12 months. That’s long before Mr. Putin decided to invade. The timing reflects too much money chasing too few goods, owing mainly to the combination of vast federal spending and easy monetary policy.

President Trump signed onto an unnecessary $900 billion Covid relief bill in December 2020, and Democrats threw kerosene on the kindling with another $1.9 trillion in March 2021. The Federal Reserve continues to support negative real interest rates nearly two years after the pandemic recession ended. This inflation was made in Washington, D.C.

Markets on Tuesday took the bad inflation report in stride, perhaps because they had (like the White House) already discounted the news. Or perhaps investors think the March report represents inflation’s peak. Oil prices may not keep rising, and the report did include some good news on used car and truck prices (down 3.8% in the month).

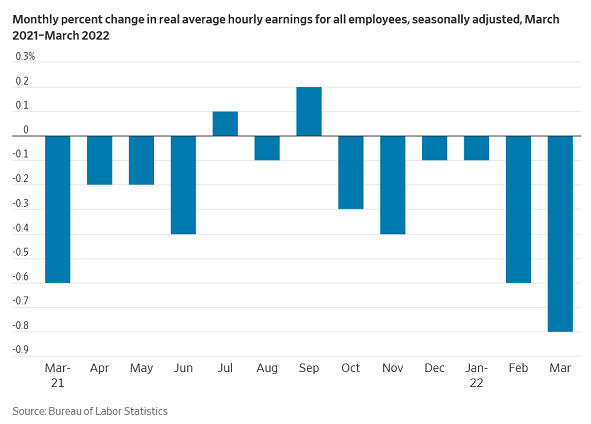

Still, the overall price news is terrible for American workers and consumers. The March surge means that real wages fell 0.8%, or a decline of 2.7% in the last year. (See the nearby chart.) Real average weekly earnings fell a striking $4.26 in March alone, and they’ve fallen nearly $18 during the Biden Presidency. If you want to know why Americans are sour about the economy even as jobs are plentiful, this is it. Their real wages are falling while the prices of everyday goods and services are rising fast. The average worker Democrats invoke when they demand more federal spending is getting crushed by the inflationary consequences of too much federal spending.

The inflation surge calls for a policy shift to tighter money and less spending that fuels excess demand. The Fed is now on the case, raising interest rates and starting to shrink its bloated $9 trillion balance sheet. Its task would be easier had it begun a year ago. Now it will have to move faster in an economy that is still growing, but with less business and consumer confidence.

Even core inflation of 6.5% is more than three times the Fed’s target rate of 2%. The Fed’s consensus target at its March meeting for a fed funds interest-rate peak of 2.8% in 2023 looks inadequate. History suggests that once inflation is this high, interest rates will have to exceed the inflation rate to break it.

That will run the risk of recession. The Fed’s anti-inflation resolve will be tested if growth ebbs and financial troubles erupt. Any central banker can cut interest rates. The Paul Volcker test of monetary mettle is raising rates when the political class is screaming at you.

As for the Biden Administration and Congress, the best anti-inflation policy would be a spending freeze on everything but defense. Cut tariffs, which would be a one-time price cut. Put a moratorium on new regulation that raises costs for business.

***

This advice conflicts with the Democrats’ Build Back Better agenda. But their inflation responses to date of allowing more ethanol fuel (see nearby) and releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve are futile gestures. Republicans could pick up the spending freeze and moratorium for their election agenda.

Inflation is a powerful political force because it can’t be explained away. Nearly every voter feels it every day. If the November elections are a referendum on the cost of living, voters won’t blame the Kremlin. They’ll blame the party in power in Washington.

The 8.5% surge in the cost of living in the past year could represent the peak of the worst U.S. inflation in 40 years — but Americans can’t expect much relief from rising prices this year or even next.

The rate of inflation has jumped more than six-fold in the past 14 months from as low as 1.4% at the beginning of 2021. The cost of fuel, food, housing, cars and all sorts of stuff have soared.

Gas prices have jumped 48% from one year ago, for example, and the cost of groceries have climbed 10% to mark the biggest increase in four decades.

“Every time you fill up at the gas station it hurts,” said Robert Frick, corporate economist at Navy Federal Credit Union. “People are going to be paying even more for meat, to which they are very sensitive.”

The sharp and relatively sudden surge caught the Federal Reserve — the nation’s guardian against high inflation — entirely by surprise. Alarmed by the spike in prices, a late-reacting Fed is now speeding up plans to lift low U.S. interest rates quickly to try to put the genie back in the bottle.

Economists predict the increase in inflation will decelerate by year end to 4% to 5%, but they say the central bank waited too long to act. It could take several years, they say, before the Fed’s bitter new medicine pulls inflation closer to its 2% to 2.5% target.

“Clearly they waited too long to get going,” said chief economist Stephen Stanley of Amherst Pierpont Securities, one of the first Wall Street pros to sound the alarm on inflation last year. “It’s going to take them awhile to catch up.”

How the U.S. got here

The roots of today’s inflation run deep.

The Biden and Trump administrations pumped trillions of dollars into the economy during the pandemic to soften the blow. At the same time, the Fed slashed interest rates to record lows and kept them there until just last month.

In short, the economy was flooded with an unprecedented amount of money.

Then as the economy reopened last spring and Americans began to spend freely again, disruptions in global trade tied to the pandemic prevented businesses from being able to obtain enough labor and supplies to meet the demand.

The combination of huge fiscal and monetary stimulus and big shortages has spawned the worst bout of price increases since the late 1970s and early 1980s, when U.S. inflation peaked at almost 15%.

High inflation is also starting to feed into the biggest increase in worker pay in decades, spawning worries about a dreaded wage-price spiral that would make high inflation more long lasting and harder to conquer.

If Americans come to expect high inflation, they’ll ask for more pay. Businesses in turn will charge even higher prices. And on and on the merry-go-round would go — until the economy crashed.

Contrite Fed officials are trying to make amends by more aggressive increases in interest rates, but most still insist that inflation will taper off relatively quickly.

The Fed predicts the rate of inflation will slow to 4.3% by year end using its preferred PCE price barometer. And then drop to 2.3% by the end of 2024.

“This is not the kind of inflation from the 1960s and 70s,” Chicago Fed President Charles Evans said on Monday.

Evans contended the current burst of price pressures is more temporary in nature. He argued inflation will revert back to the low levels that prevailed before the pandemic in a year or two.

Fed officials are likely to take solace from a small 0.3% increase in March in a closely follow inflation barometer known as core consumer prices. It matched the smallest gain in six months.

Yet just as it took time to reduce inflation four decades ago, most economists predict a longer road ahead than the Fed expects.

“The Fed is still largely expecting inflation to self correct and mostly go down on its own,” said chief economist Aneta Markowska of Jefferies, another Wall Street analyst who raised questions about rising prices early on last year.

“I think they are too optimistic on inflation coming down.”

Is the worst over?

So why does the Fed and so many economists — even skeptics like Stanley and Markowska — expect the rate of inflation to slow this year? They think the inflation wave either crested in March or will do so in April. Some like UBS even see the runup in prices mostly reversing by year end.

Fed interest rate hikes this year might restrain inflation a little by making big-ticket items like new houses and autos more expensive, for one thing.

More importantly, the supply-chain bottlenecks that have contributed so much to high inflation are expected to continue to ease.

If businesses can obtain more supplies, the thinking goes, they won’t have to pay as much for materials or charge customers as much for their goods and services.

Finally there’s a statistical mirage of sorts known in economist lingo as “base effects.” As high monthly inflation readings from last year drop out of the 12-month average, it makes headline inflation seem lower.

Take last June, when the consumer price index leaped 0.9%. If several months from now, the CPI rises, say, 0.5% in June, it would make the yearly increase in inflation look smaller.

It wouldn’t necessarily mean that price pressures are easing, though.

A half-point increase in monthly inflation is still historically high, for one thing.

What’s more, the annualized rate of inflation in the first three months of 2022 is still extremely troublesome at 11.3%. That’s how much inflation would rise this year if it increased at the same pace in the final nine months as it did in the first three.

Then there’s the war in Ukraine and Covid lockdowns in China, both of which could exacerbate inflation in the short run.

Russia is a major producer of oil and grains and Ukraine is also a large grain grower. The war has added to the upward pressure on fuel and food prices and the effects could persist well after the conflict is over.

In China, factory closings and the lockdowns affecting millions of people could stanch the flow of goods to the U.S. and put renewed stress on strained supply lines.

The Fed’s big challenge

The real fight to significantly lower inflation is in 2023, economists say. And one of the most “dovish” Feds in history, as Stanley calls it, will only achieve some success if it is aggressive.

That could mean raising a key short-term U.S. interest rate above the central bank’s current goal of 2.8% by the end of 2023 — and possibly slowing the economy to the point of recession.

“Inflation is likely to decelerate, but left on its own, not very rapidly,” said Joel Naroff of Naroff Economic Advisors.

He said there’s still too much demand that businesses can’t meet, a problem that would only be rectified by the Fed icing down a hot economy.

Yet even an aggressive central bank may be limited in what it can achieve quickly. Markowska pointed to a New York Fed study showing consumers think inflation will rise 6.6% in the next year — the highest reading on record.

What do Americans plan to do in response? Keep spending, the survey shows.

Many households have the means to do so.

Wages, for example, have jumped 5.6% in past year to mark the biggest increase in decades and help Americans cope with a higher cost of living. And thanks to unprecedented government stimulus, Americans have an extra $2 trillion-plus of savings in the bank than they did before the pandemic.

“Nobody likes to pay higher prices. The question is, what are consumers going to do about it,” Markowska said. “They are not pushing back at all. They are paying higher prices and moving on.”

If that keeps up, though, Americans will have to use up their savings and eventually find other ways to afford the higher cost of fuel, steak or a beach vacation.

“That’s when you walk in and say to your boss, ‘I need a raise,’ ” Stanley said.

While rising pay would be a good thing for workers, it would give companies even more reason to raise prices and prolong the bout of high inflation.

“I think inflation is going to be around 3% to 4% around the end of the year, but stay stubbornly high relative to the preceding decade,” said Steve Blitz, chief economist of TS Lombard.