Vi presentiamo in lettura un articolo di Barron’s. Forse, l’articolo più significativo che Recce’d ha letto nel 2022.

Il titolo di Barron’s si richiama al tema di cui si parla di più in questo momento tra gli operatori di mercato: la recessione.

Chiariamo subito: da questo punto di vista l’articolo che segue a noi di Recce’d NON interessa: Recce’d NON condivide ciò che viene detto nell’articolo a proposito della recessione.

Ma ci sono altre cose interessanti, ed importanti: e sono molte.

Le elenchiamo prima di lasciarvi alla lettura:

secondo noi è importantissimo, e diremo FONDAMENTALE per il nostro mestiere, quello che viene detto a proposito di “come si fanno le previsioni”

è utilissimo rileggere del tema degli Anni’20, tema che andava di moda tra operatori e banche di investimento solo sei mesi fa

ovviamente è utile anche leggere ciò che vene detto degli Anni Settanta (tra parentesi, una interpretazione che Recce’d NON condivide)

è molto utile leggere ciò che si dice sui fattori da cui si origina l’inflazione di oggi

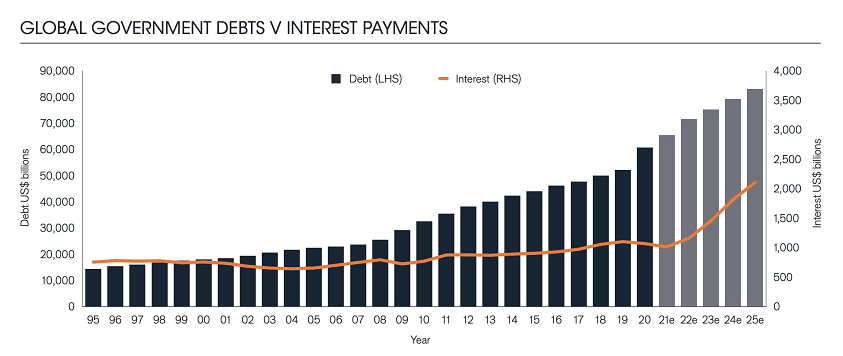

è utile riflettere sulle affermazioni in merito a quello che i mercati finanziari oggi hanno già scontato nei prezzi (un rialzo dei tassi ufficiali allo 2,50%) e in merito alla sostenibilità del debito negli Stati Uniti (anche qui, Recce’d NON condivide questa analisi)

infine, un punto che (come sanno benissimo tutti i nostri Clienti) è centrale nella nostra strategia di investimento da ormai due anni: il “ritorno alle cose reali”. Da questo ritorno, deriverà un altro ritorno: il notevole ritorno che i nostri portafogli modello genereranno per i nostri Clienti nel 2022, nel 2023, nel 2024.

Vi proponiamo quindi di leggere l’articolo che segue con grande attenzione (eventualmente facendovi aiutare da un traduttore dal web) e poi riflettere sulle vostre attuali posizioni investite sui mercati finanziari. Noi di Recce’d siamo qui, se desiderate per approfondire e consigliarvi.

When a prominent economist predicts an event will drag down growth by 0.3 percentage point, TS Lombard global macro strategist Dario Perkins usually gets a few social-media alerts thanks to one of his most popular writings.

The piece, a tongue-in-cheek guide to banks’ economic research, calls out 0.3-percentage-point predictions as a commonly used trick of the trade. Also on the list: making radical forecasts but assigning them a 40% probability, and warning of recession dangers while assuring readers the economy looks good for the next 18 months.

“If something happens in the world, and you ask an economist about the impact, they will always say 0.3 percentage points,” says the 43-year-old Perkins, a managing director at the London-based macroeconomic forecasting firm. “The reason is that it’s significant, you can see it, but it doesn’t change everything. It allows this false sense of precision.”

Luckily, he has room to reject the conventions of the forecasting business, after spending a few years as a top-ranked economist at ABN Amro and working for the U.K. Treasury. Rather than providing vague warnings about the dangers of future recession, Perkins says the European economy is already contracting.

He recently chatted with Barron’s on Zoom from his home in a Kent town that he shares with his wife and three children, discussing global inflation, rising interest rates, the 1970s, and the “Tangible ‘20s.” An edited version of our conversation follows:

Barron’s: Between the reopening from Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, how are you looking at the global economy right now?

Dario Perkins: Before this crisis in Ukraine, this was the hardest economy to interpret that I’ve seen in my career. In late 2020 it was very hard to tell whether the world had totally changed during the pandemic, or whether people were over-extrapolating from massive Covid-19 distortions. And it seemed weird to think that you could just shut down an economy completely, reopen it, and then extrapolate from that reopening process into this idea of the Roaring ’20s.

Nobody’s talking about the Roaring ’20s anymore, but that was certainly a big topic last year, wasn’t it? You can debate about whether the U.S. economy was overheating because of tighter labor markets and wages, but in Europe, there’s been no sense of overheating at all. And now clearly there are lots of people in Europe who are going to really struggle with the fact that 50% of our energy’s just gone up massively in price. The difficulty here is we just don’t know how long this situation is going to last.

Do you think Europe could go into a recession? Where would we see the early signs of that?

The European economy is probably contracting right now, because inflation is hitting 7% to 8% and wages are going up 1%. People are getting very squeezed by this and we’re not yet seeing it in the data because it’s too early. But certainly there’s been a short-term contraction in the economy—it’s just whether it spills over into a deeper, broader problem. There’s still a good chance that we can shake this off.

If this [invasion is] over, the slowdown is going to fade very quickly. If this goes into months, then the chance of a broad recession in Europe suddenly increases a lot.

And the war makes inflationary pressures worse too, right? Between the potential for a slowdown and high inflation it can’t be easy to be a central banker right now.

You know, [central bankers] take a lot of credit for the fact that inflation has been low over the last 30 years, and they attribute that to their credibility. If you’re a central banker, your big fear, even six months ago, was that you were making the same mistakes that policy makers made in the 1970s. Central bankers have been brought up with the ’70s as this cautionary tale of what can go wrong if a central banker doesn’t do the appropriate things when inflation starts to appear.

I don’t think you can be a central banker and not look at this situation and think, ‘oh my God, is it happening again?’ … You see a global energy crisis with inflation that’s already very high and about to suddenly get higher, and that echo suddenly starts to feel even stronger.

Do you think that the 1970s comparisons are warranted?

Well, there are some superficial similarities with the 1970s. The first is the energy price shock. That’s happening against a backdrop where you already had an inflation problem. … And central banks were first inclined to dismiss it rather than react to it. Those are the similarities. I would say those are mostly superficial.

The big difference is institutions. We’ve spent the last 40 years dismantling the institutions that gave us that inflation in the 1970s, because that inflation, it changed everything. We took apart that post-World-War-II economy. We destroyed worker power. We destroyed trade unions. We banned wage indexation. We opened up product markets. We created this globally competitive world.

To me, the 1970s were all about this power conflict between labor and capital. There was a young, militant, unionized workforce. They were making excessive wage demands, because they didn’t want to accept the slowdown in productivity. Companies were protected from global competition and had simple pricing mechanisms like cost-plus pricing—whatever cost they faced, they just added on a margin and passed it on. So an automatic spiraling of wages and prices came out of that conflict. It’s very unlikely that we see those kinds of dynamics again.

But wages are rising, right?

Today, at the low end of the skill spectrum, you’re seeing workers getting big pay raises because there’s been a reluctance of people to return to those occupations after Covid-19 closures. That has created some worker power in certain sectors of the economy and fed through into wages, but I don’t think that’s going to lead to spiraling.

The minimum pay of people in those sectors has gone up, and it’s never going to go back down again. But it isn’t going to keep rising 10-15% year after year. Still, there is an element of power there.

You mentioned another way things are different today—companies are now globally competitive. How do companies fit into all of this?

There’s an element of power in the corporate sector as well. Over this [pandemic] period, companies have discovered that they can pass on cost pressures. But the question that’s really difficult is whether that is specific to the Covid era, or whether that’s some kind of cultural change.

On one side, you could say, companies have discovered that actually they can raise their prices, and consumers will accept it, so they’ll just keep increasing prices. That would be the thing that would worry central bankers. And when you look at the last two earning seasons in the U.S., you certainly have companies bragging about their pricing power. Not just saying they have it—actually bragging about it.

But everybody knew that companies were under all kinds of cost pressures because of the pandemic, so consumers accepted it, because they understood that this was a weird kind of bizarro world that we were in.

Still, if there’s one area where I could be wrong—that’s the thing that worries me the most, this shift in the cultural acceptance for prices going up. And it’s not something that we can really measure, so we’re only going to know over time. If I were a central banker, that’s what I would be more worried about than some kind of wage-price spiral that comes from workers demanding too much money.

If there’s no wage-price spiral, where do you think inflation goes from here?

My bet is that inflation will come down quickly, once we get through all of this mess.

I’m still kind of on Team Transitory, even though you can’t say that anymore. You should never say you’re on Team Transitory. I don’t think that central banks have to be much more aggressive to try and force inflation down.

Some argue that because inflation is so strong now, that means it’s already too late, right? How will central bankers get prices under control?

Central banks want to get back to some kind of neutral policy. It’s not that they think inflation is going to spiral higher, but they think that’s a risk, and they think they’re badly positioned to deal with that risk because they’ve still got these emergency levels of interest rates.

There’s an almost automatic desire to get interest rates up. If the Fed can get back to interest rates of 2.5%, which is roughly neutral … lot of policy normalization is already priced in. Markets have already absorbed the idea that interest rates are going up very rapidly.

Looking beyond that, we’re wondering, where does inflation settle? And what will central bankers do? If inflation drops below 4% and stays there, that’s a tolerable level of inflation. It’s above target, but they undershot their target for the best part of 20 years, so having a few years of 3.5% inflation isn’t going to make a huge difference. Central bankers would probably bite your hand off if you offered it to them right now.

If inflation settles above 4%, I don’t think they would tolerate that. If you look at Fed history, 4% inflation seems to be the cutoff between when they start to panic and become much more aggressive. Really, the only way to do that is to cause unemployment to go up, but unemployment only ever goes up in a recession. So really, that is a dynamic where the Fed would have to engineer a recession to get inflation down.

Some Fed watchers believe that officials won’t be able to raise interest rates too high without causing a recession. Are you worried about the sustainability of debt as interest rates go up?

I’ve done a lot of work on debt sensitivity of different countries. … The economies that look the most sensitive to rates going up are the ones that didn’t have a problem in 2008, because they’ve just continued to leverage up. Those will probably blow up well before we start to see real problems in the U.S.

In Canada, for example, when interest rates start to go up even a little bit, we start to worry about debt servicing costs, because they’ve accumulated so much debt over the last decade… there’s a huge amount of household debt, a huge amount of corporate debt, the debt that’s been taken on is all variable rate, and then they just had this massive housing boom… there’s this real vulnerability from all this borrowing that’s been happening in Canada.

But the U.S. has done a lot of deleveraging, so I’m not sure that the real economy is sensitive to interest rates going up. Central bankers can just about pull off a soft landing. But if inflation stays too high, then the chances of them pulling it off are pretty much zero at that point.

Another one of your tips for bank economists is to avoid making market predictions. But I have to ask: Do you have any views on global markets right now? If rates are going up and central bankers pull off tightening without a recession, where should people be investing?

The really important thing is that fiscal policy globally is going to have to play a much bigger role than it did over the last decade. … That will give you a different type of stock market. The [recent] rotation from growth to value, that’s a secure theme. I think that’s going to be the theme of the 2020s, actually.

We’re not going to have zero interest rates forever. Defense and industrial spending, infrastructure, climate change investment, housing—these are all real-economy [growth] impulses. These are the Tangible ’20s. It’s the return of value, the return of tangible investment, the return of real things.

That’s a better dynamic for real people, and it doesn’t make me bearish on the stock market. It’s not bullish for [big tech stocks], but it’s bullish for the stock market in general. And it’s bullish for society, because all of the problems that we’ve had over the last decade—inequality, stagnant wages, polarization, you know—these were things that we couldn’t address with monetary policy. If you’re going to start to use fiscal levers more, you can actually start to challenge those problems.