Come abbiamo scritto già nelle due settimane precedenti, in Recce’d seguiamo con particolare attenzione l’Europa in questo momento.

Ciò che vediamo negli Stati Uniti, per noi rientra nel prevedibile: non ci stupisce e quindi non ci colpisce. Non dobbiamo spiegare nulla ai nostri Clienti, che erano (da tempo) preparati.

In Europa, a noi sembra che la situazione sia diversa, e da più di un punto di vista.

Spieghiamo: le ricadute di ciò che vedete succede sui mercati finanziari, per l’Europa e per la zona Euro in modo particolare sono più ampie, rispetto alla situazione degli Stati Uniti.

Anche negli Stati Uniti vedremo ricadute sulla vita sociale e politica. Ma in Europa potrebbero essere più profonde.

Ne scriviamo da una settimana, ogni mattina nel The Morning Brief per i nostri Clienti.

Con questo Post, noi vogliamo mettere all’attenzione dei nostri lettori soltanto uno, dei tanti aspetti che a noi fanno ritenere particolarmente delicata la situazione dell’Europa e dell’Area Euro in questo momento.

Si tratta del conflitto in Ucraina.

Già nel mese in febbraio, ed anche in forma pubblica attraverso questo Blog, Recce’d scriveva che questa guerra tra Ucraina e Russia è “una cosa per il lungo periodo”.

Oggi, ritrovate il medesimo concetto scritto sulla stampa nazionale ed internazionale (immagine qui sopra.

I mercati finanziari, e noi investitori, siamo chiamati a fare i conti daccapo, a rivedere tutte le stime, non solo epr il 2022 ma per il medio termine.

Allo scopo di fare proprio questo, Recce’d ha selezionato per i suoi lettori un recente articolo del Financial Times, che vi aiuterà a capire in che modo siamo tuti costretti a modificare i numeri, le stime e le previsioni per le economie europee, e quindi per conseguenza anche per i mercati finanziari europei.

Nell’articolo scritto da Martin Wolf potrete leggere in particolare le ragioni per le quali, per l’Europa, le conseguenze della guerra in Ucraina sono economiche ma anche politiche e morali.

How should the EU manage the economic costs of Vladimir Putin’s war? That is not the same as minimising those costs. This is a war, one on which the future of Europe, perhaps of democracy itself, will depend. In such times, the aim of economic policy is to support the war effort. Policy should seek to maximise costs to the aggressor relative to those to the EU, particularly to its most vulnerable citizens. How should this be done? If we are to think about this question, we need an analytical framework. Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the IMF, and Jean Pisani-Ferry provide that in a recent paper.

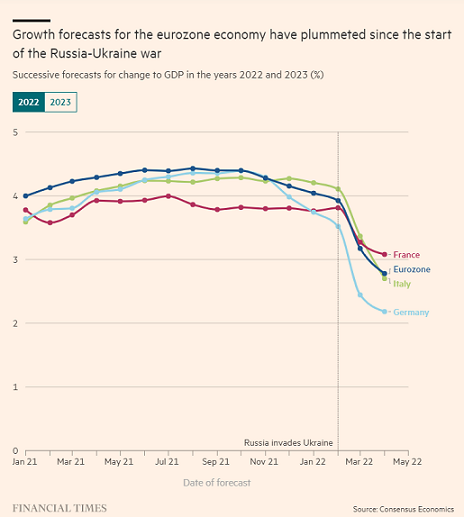

They list three challenges: first, “How best to use sanctions to deter Russia, while limiting adverse effects on the EU economy”; second, how to deal with cuts to real incomes that result from the rise in the cost of energy imports; and, third, how to manage the increased inflation caused by higher energy and food prices, which has come on top of the post-Covid surge in inflation. Needless to say, any such analysis is provisional. In times of war, the future is even more uncertain than usual. (See charts.)

On the impact of sanctions on Russia, consider a recent comment by Rystad Energy: “Despite the severe oil production cuts expected in Russia this year, tax revenue will increase significantly to more than $180bn due to the spike in oil prices . . . This is 45 per cent and 181 per cent higher than in 2021 and 2020, respectively.”

This is not to deny the damage done by sanctions: the IMF forecasts that Russia’s economy will shrink by 8.5 per cent this year. But it means that higher prices are more than offsetting reductions in volumes. Consumers are suffering, but they are also financing the invasion of Ukraine.

This is bad policy. The aim must at the least be to lower the revenue Russia receives from its exports, not increase it. A number of economists have considered what this might require.

Seven points emerge from their analyses.

First, the EU’s vulnerability to Russia, but also power over it, is greater in gas than oil, because gas depends more on a fixed infrastructure. That makes diversification of sales by Russia (though also of purchases by the EU) more difficult.

Second, the most effective way to lower revenue to Russia is not an embargo but a punitive tax or tariff, which should shift Putin’s “energy rent” to consumers.

Third, imposing tariffs would generate revenue that can be used to help those suffering losses in real incomes at present.

Fourth, a tax imposed by the EU alone on Russian exports would achieve more in gas than in oil, because of the greater difficulty of diversifying gas exports.

Fifth, trade sanctions would be more effective the greater the number of participating countries.

Sixth, one might extend sanctions on oil by placing sanctions on shipping. Finally, the cost of such measures to Russia would be a large multiple of their costs to the EU and allies. Reaching consensus on effective measures is hard, but crucial.

A way has to be found to shift more of the revenue of Russian exports to consuming countries. Yet, whatever is done on that, there will be significant costs to wealthy importing countries from the war: increased spending on defence; greater spending on energy infrastructure; assistance to refugees; and, not least, substantial support for hard-hit developing countries. Inevitably, the salient political issue will be how to cushion the blow to domestic consumers.

Should this be done via subsidies on energy, transfer payments or price controls? A big part of the answer depends on the sanctions regime that is adopted. But the general point is that subsidies will tend to offset sanctions by increasing consumption rather than reducing it. It would be better to increase transfers of purchasing power to vulnerable households, leaving them to decide how to spend it.

Price controls on oil were a disaster in the 1970s. I can see no good reason why they would do any better now. If one wants to limit windfall profits, it would be better to tax them. How, also ask Blanchard and Pisani-Ferry, should transfers or other spending measures be financed? Since a war is a short-term emergency, the case for additional government borrowing is strong.

Moreover, at current long-term interest rates (still very low) and prospective increases in nominal gross domestic product (boosted by inflation), extra debt would be affordable.

This then raises the issue of monetary policy. The impact of the war is to strengthen upward pricing pressures, risking an inflationary wage-price spiral, while simultaneously weakening demand as real incomes are squeezed. Blanchard and Pisani-Ferry suggest these two effects offset each other. In that case, they argue, monetary policy should remain on the tightening path laid out before the Russian invasion. But they also suggest fiscal measures might be targeted at lowering price inflation, so reducing the risks of the wage-price spiral. They also suggest that such fiscal measures could be brought into the wage-bargaining process directly. I am sceptical. Yet it just might work in northern Europe.

The conclusion I draw from these analyses is that the war is a significant economic shock, but it is very much more a political and moral one. A brutal conflict has come to Europe of a kind not seen since the second world war, and even where some of its worst atrocities occurred. For Germany in particular, it is a moment of challenge and opportunity. The challenge is to defend Europe’s liberal civilisation. The opportunity is for historic redemption. Russia must not prevail. This is what matters most. There will indeed be pain. But it must be borne for a far greater cause.

martin.wolf@ft.com Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on Twitter