Come vedete qui sopra, gli interventi fatti in settimana dalla Federal Reserve hanno riportato il costo della liquidità interbancaria al livello di 12 mesi prima.

Noi fin dalla metà di settembre abbiamo commentato con frequenza giornaliera per i Clienti in The Morning Brief ciò che sta succedendo sul mercato interbancario degli Stati Uniti, e abbiamo tratto questo argomento anche sette giorni fa in questo Blog.

Continueremo a seguire il tema e a lavorarci, a favore dei nostri Clienti, perché siamo certi che il tema resterà di attualità anche dopo che i tassi di interesse sul mercato monetario sono scesi.

Le implicazioni di questo episodio sono state del tutto fraintese, dalla maggior parte dei commentatori (sotto, il titolo fatto pochi giorni fa dal Corriere della Sera) e hanno nulla a che vedere con le difficoltà di una singola Istituzione: si tratta di implicazioni che riguardano l’intero sistema finanziario degli Stati Uniti, e che vanno anche oltre. In particolare, la crisi della liquidità interbancaria è un tema che si intreccia con il tema della crescita del deficit pubblico negli Stati Uniti.

In questo senso, è un tema che presto interesserà anche l’Eurozona.

Recce’d come detto continuerà ad analizzare gli sviluppi di questa situazione su base quotidiana in The Morning Brief. In Questo Post, però, offriamo ai lettori un utile contributo alla comprensione, nella forma di due diversi commenti abbiamo selezionato per voi e che leggete qui sotto.

Il primo commento mette in evidenza la stretta connessione tra la crisi del “repo market” e il deficit pubblico degli Stati Uniti, in modo molto efficace.

The repo market madness lives on for a ninth day.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York announced Wednesday that it would increase the size of its next overnight system repurchase agreement operation to a $100 billion maximum, from $75 billion previously, and also raise the limit on its 14-day term repo operation to $60 billion from $30 billion. Simply put, the bank wants to flood the funding market with enough cash to soak up all the securities that dealers submit 1 and leave no doubt that the critical financial-system plumbing is in fine working order ahead of the end of the quarter.

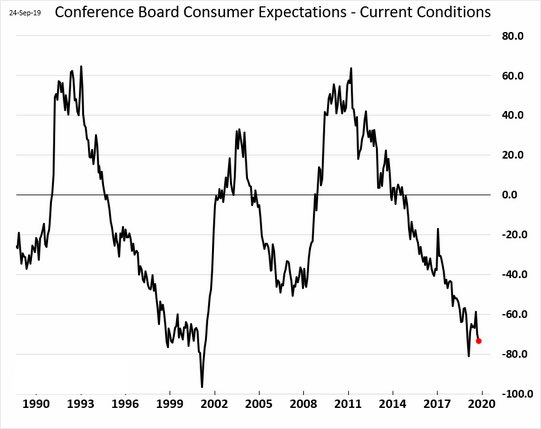

By now, just about everyone has heard the explanations for this persistent liquidity squeeze, which has lasted long enough to refute the earlier notion that it was merely a one-day confluence of unfortunate events. To some, the main structural issue is that banking regulations are disrupting the financial system’s inner workings. Others say the Fed has simply found the lower bound for reserves necessary to control short-term rates and can move forward accordingly.

In addition to those two assessments, I’d offer another angle that’s largely flown under the radar: The chaos in repo markets was a long time coming given the widening U.S. budget deficits and the lenders that are financing that shortfall.

Deficits, while nothing new, add up over time. And while they declined each year from 2011 through 2015, both overall and as a percentage of gross domestic product, the gap has widened again under President Donald Trump. Put it all together, and the amount of U.S. Treasury securities outstanding has roughly tripled since the financial crisis:

This growth was mostly under control in the years after the financial crisis because the Fed had been buying up large chunks of the Treasury market through its quantitative easing programs. But it was gradually reducing the size of its balance sheet from late 2017 until July, precisely at the same time that the Treasury Department was increasing the size of its monthly auctions to finance the bigger budget shortfalls. All told, the Fed now holds about $2.1 trillion of Treasuries, down from almost $2.5 trillion previously:

The Fed remains the largest single holder of Treasuries. But combined, Japan ($1.13 trillion) and China ($1.11 trillion) own more. And yet, even with those huge stakes, the two countries haven’t been keeping up with the growth in the world’s biggest bond market. In fact, on a percentage basis, Japan’s U.S. Treasury holdings are close to the lowest in at least 20 years, while China’s are the lowest since mid-2006:

So if it’s not the Fed, it’s not China and it’s not Japan, where are all these Treasuries going?

U.S. commercial banks are certainly a place to start looking. They’ve done their part since the financial crisis, but especially lately, with holdings of Treasuries and agency securities climbing to almost $3 trillion as of Sept. 11:

Primary dealers, a select subset of banks that are obligated to bid at Treasury auctions, were saddled earlier this year with the most Treasuries ever — an outright position of almost $300 billion. Even now, their holdings are more than double what they were a year ago as they’re required to take down larger pieces of the U.S. government’s debt sales.

There are simply too many bonds (or, in the language of the repo market, “collateral”) sloshing around in the financial system and not enough cash on the other side of the trade. America’s budget deficits are being financed domestically and leading to a relentless drain on reserves:

All this goes to show that fiscal stimulus — which I’ve argued that bond markets are begging for — doesn’t quite work by itself. Without the Fed helping to finance deficits by accumulating Treasuries, the financial system seems doomed to seize up. Someone has to take what the Treasury is offering, and given that the 24 primary dealers are by definition the buyers of last resort, it falls on these critical institutions to pick up the slack.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon said that the banks “have a tremendous amount of liquidity but also have a tremendous amount of restraints on how they use that liquidity.” As former Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota wrote for Bloomberg Opinion, requirements like holding a certain amount of liquid assets and maintaining a minimum leverage ratio, which sound perfectly reasonable in theory, can distort lending and borrowing in unforeseen ways.

Boiling down the New York Fed’s repo operations to their most basic level, the central bank is effectively coming into the market every morning, taking excess securities from dealers and giving them cash instead. This is a quick fix to offset the liquidity imbalance, but it’s not a permanent solution. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said last week that it’s “certainly possible that we’ll need to resume the organic growth of the balance sheet earlier than we thought,” and indeed it seems likelier by the day that policy makers will announce such a move by their next interest-rate decision on Oct. 30.

Wall Street strategists have gone to great lengths to say that such organic growth is not QE. I’m fine with that distinction. But ultimately it comes down to the fact that the Fed seems to have little choice but increase the size of its balance sheet in the face of trillion-dollar budget deficits, whether in good economic times or bad ones. U.S. banks can’t afford to have the Fed out of the market entirely.

The financial system, as it is today, is choking on Treasuries. And only the Fed can perform the Heimlich.

Il secondo estratto, scritto da un ex Presidente della Federal Reserve a Minneapolis, mette invece in evidenza il ruolo della regolamentazione dell’operatività delle banche. Anche questo è un tema che diventerà a breve importante anche in Eurozona. Una situazione che il bazooka di Draghi ha sicuramente peggiorato.

The recent unrest in money markets, which briefly caused short-term interest rates to get out of the Federal Reserve’s control, won’t undermine the central bank’s ability to achieve its longer-term economic goals. That said, it does signal that something’s very wrong with the financial system.

To understand what’s going on, let’s return to a simple model. Suppose there’s only one big bank. It has a choice of what to do with most of its assets: It can keep them on deposit at the Fed, earning the interest rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves; or it can take more risk and earn more return by investing in securities or loans. In this world, all the assets earn the same “risk-adjusted” return, which the Fed effectively determines by setting the interest rates on excess reserves.

Now let’s take a step closer to reality. There are two groups of banks, “tight” ones that hold few excess reserves, and “flush” ones that hold a lot. Flush banks can lend reserves to tight banks in the federal funds market, a focal point of the Fed’s monetary policy. As long as this lending happens freely, all assets will still have the same risk-adjusted return, and the one-bank model will still be a good indicator of how the many-bank world will respond to the Fed’s policies and to various shocks.

In recent days, though, that crucial free-lending condition hasn’t held. On the contrary, a convergence of events -- a deadline on corporate-tax payments and the settlement of a big Treasury auction -- created a sudden and severe shortage of reserves. As a result, interest rates diverged sharply in markets where they should be the same. In the repo market, where participants borrow and lend against the collateral of Treasuries and other securities, they shot up above 5%. And in the federal funds market, they breached the upper bound of the Fed’s 2%-to-2.25% target range.

The deeper issue is that, since the 2008 crisis, regulatory reforms -- such as requirements that banks hold a certain amount of liquid assets, and maintain a minimum leverage ratio (equity capital as a percent of total assets) -- have constrained the ability of flush banks to lend, and of tight banks to borrow. Such constraints interact in complicated ways with financial market conditions. For example, European banks must report their leverage ratios as of the last day of each quarter, so they reduce their repo activity to make those ratios look better. As a result, even when excess reserves seem abundant, funding costs for banks may exceed the interest rate that the Fed controls.

This isn’t necessarily a problem for the Fed’s monetary policy, because the central bank can inject cash into various markets to bring interest rates into line. That’s precisely what the Fed has been doing in the repo market. And it can make the fix more permanent by creating what’s called a standing repo facility, which means the Fed will inject sufficient funds every day, as needed, to ensure that the federal funds rate stays in what it deems the appropriate range.

What’s harder to understand is how money markets will respond to future shocks. As the experience of the past couple weeks has shown, the simple single-bank model no longer works. Reserves are siloed in the flush banks, so the financial system is acting more like it has $1.3 billion in excess reserves than the actual $1.3 trillion. The design of regulation has disrupted some of the system’s most basic functions. The people who oversee it all should be far from sanguine about what the repercussions might be.