Siamo stati, noi di Recce’d, sempre molto critici verso la persona, e la figura di Mario Draghi.

Nel 2015, al tempo del “bazooka” fummo tra i pochissimi a scrivere che quel “bazooka” non esisteva, e che la mossa del 2015 aveva finalità molto diverse da quelle dichiarate. I fatti ci diedero ragione: è stato così.

Nelle settimane del suo insediamento a Capo del Governo, scrivemmo più volte che Draghi era semplicemente una operazione di Palazzo, o se preferite del Sistema, per salvaguardare sé stesso, operazione che non avrebbe mantenuto le tante (davvero troppe) promesse diffuse e vendute al pubblico.

Eravamo soli, allora: e le nostre prese di posizione furono trattate come una sorta di “tradimento della Patria”.

I fatti anche in questo caso ci hanno dato ragione.

Oggi, con questo Post, intendiamo prendere la posizione opposta: vogliamo prendere le parti di Mario Draghi.

Questo perché siamo irritati dal vero e proprio diluvio di commenti caustici e sarcastici che si leggono sui social e che attaccano la persona di Mario Draghi dopo che lo spread tra Titoli di Stato italiani e tedeschi è ritornata ai livelli del 2019 e dopo che la Borsa italiana è ritornata a scendere del 5% in un solo giorno.

Sui social spopolano, in questo weekend, immagini come quella qui sopra, ed altre immagini come quella qui sotto, che sembrano attribuire proprio a Mario Draghi l’innalzamento dello spread.

Ma si tratta di una atteggiamento polemico, superficiale, e anche un po’ stupido.

Che cosa ne può, Mario Draghi? Non ne può nulla.

E’ importante chiarire subito: Recce’d in questo post afferma che Draghi non ha responsabilità dirette, nel rialzo dello spread.

Certo, non si può negare, è a capo del Governo. E non si può negare che il suo Governo, a proposito di questo problema, ha fatto ben poco. Diciamolo pure: ha fatto nulla.

Il problema, che tutti conoscono, è sempre il medesimo problema: è il problema di un anno fa, di due anni fa, di cinque anni fa, di undici anni fa.

Non è, quindi, e non può essere, un problema di Mario Draghi: è il problema di tutti i Governi che si sono succeduti negli ultimi decenni, di centro sinistra, di centro destra, giallo-verdi, e pure dei Governi tecnici.

Nessuno, di questi Governi, e dei personaggi che hanno guidato questi Governi, ha fatto nulla. Solo, e sempre, operazioni di facciata, di abbellimento: nessuno di questi signori ha mai chiamato il problema con il suo nome, con la sola esclusione, almeno nei primi mesi, di Mario Monti.

Tutti invece impegnatissimi a girarci intorno.

E quindi, a tutti gli spiritosi e a tutte le belve da tastiera che si accaniscono sui social, chiediamo: chi avreste messo, voi, al posto di Mario Draghi, allo scopo di evitare questo rialzo dello spread?

Oppure: credete davvero che il rialzo dello spread sia la conseguenza di un “complotto plutocratico internazionale” che ha lo scopo di danneggiare proprio noi italiani? Per rendere gli italiani il popolo schiavo delle Potenze straniere?

Ma di quali potenze? Ma schiavi per fare cosa? Per raggiungere quali obbiettivi? Siete davvero convinti che ci sia la fila di gente che non vede l’ora di assumersi la responsabilità di mettere energie, attenzione, ed impegno in questo nostro Paese così come è oggi? Noi siamo sicuri di no: siamo sicuri che preferirebbero, giusto per dire, la Grecia o la Turchia. C’è meno … casino, sarebbe più facile.

Noi adesso ritorniamo a scrivere di Mario Draghi: che non merita tutto l’astio di cui è fatto oggetto sul piano personale.

Ha fatto poco, da Capo del Governo, e forse nulla a proposito di questo problema. Ma resta il fatto che quando è stato portato a Capo del Governo era la migliore delle alternative possibili, o sarebbe meglio dire la meno peggiore. Ci hanno messo lui, perché non c’era proprio nessun altro. Rendetevene conto.

Oggi Draghi subisce questo diluvio di attacchi astiosi soprattutto a causa delle aspettative che erano state create: da questo punto di vista, i suoi “presunti amici” sono stati i suoi peggiori nemici.

Spieghiamoci con un esempio, che vedete nell’immagine qui sotto.

C’è ancora oggi chi tenta di confondere le idee al pubblico, e pretende che i lettori dei quotidiani siano degli autentici imbecilli: come chi oggi scrive che il rialzo del tassi ufficiali annunciato giovedì 9 giugno dalla BCE sia la conseguenza di un “complotto di Putin”.

E’ una sciocchezza così grande, che sarebbe da riprendere in un programma comico alla TV, del tipo Zelig.

Eppure, viene ripresa anche da altri quotidiani, come leggete nell’immagine che segue.

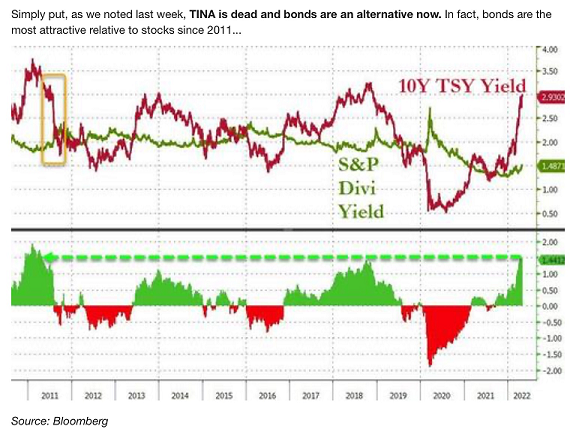

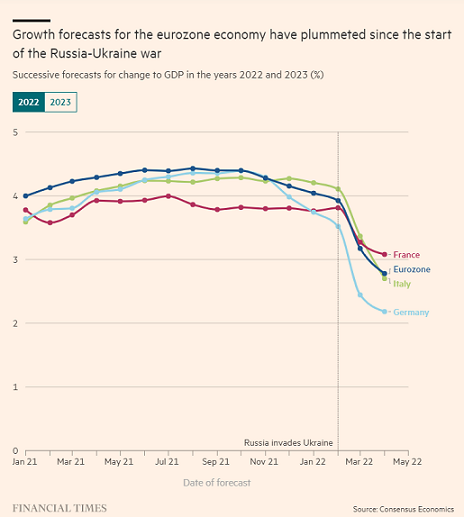

La decenza professionale vorrebbe che quotidiani nazionali, come sono Il Corriere della Sera e La Stampa, per rispetto dei propri lettori accompagnassero gli articoli di commento che abbiamo appena riportato con il grafico che trovate qui sotto.

Non solo: il grafico dovrebbe essere spiegato ai lettori dei quotidiani citati, allo scopo di aiutarli a comprendere ciò che accade oggi, e ad anticipare quello che accadrà domani.

Questo si dovrebbe fare, se si avesse rispetto dei propri lettori. Invece di inventare favolette a scopo consolatorio, inventarle allo scopo di prolungare per il maggiore tempo possibile gli attuali (fragilissimi) equilibri del potere politico.

Lo scopo di proteggere l’equilibrio in essere nel mondo della politica va però in contrasto con i titoli, inevitabilmente allarmistici, che raccontano la realtà dei mercati finanziari.

I prezzi che si leggono sui mercati finanziari non forniscono alcun appiglio, ed anzi appaiono in totale contrasto, con la buffa teoria del “complotto di Putin”.

Il Corriere della Sera si spinge persino a scrivere, come leggete sotto nell’immagine, che “ora per l’Italia cambia tutto”.

Qui l’artificio e l’inganno sono ancora più evidenti: perché “ora” per l’Italia non cambia nulla, perché “ora” non c’è stato alcun aumento dei tassi. Arriverà poi. Ma soprattutto, perché la realtà in questo modo viene capovolta: il problema è che “ora”, ma pure 12 mesi fa, e 24 mesi fa, e 36 mesi fa, per l’Italia non cambia mai nulla.

Si tira avanti, fingendo che i problemi semplicemente non esistano e si punta tutto sul prendere tempo. Si sta lì fermi a fare niente, magari sfogliando in poltrona il Corriere della Sera. Così ha fatto anche Mario Draghi, e tutti gli altri che lo hanno preceduto.

Non cambia mai nulla: ed infatti riappaiono gli articoli del 2011 che raccontano del Governo Berlusconi e della “Lettera da Bruxelles” che ne determinò la caduta rovinosa.

Quello fu senza dubbio un episodio che vide la BCE coinvolta in dinamiche di tipo squisitamente politico: non fu il primo, non sarà l’ultimo. Accade in Europa, accade negli Stati Uniti.

Un Governo valido e capace riesce a non fare precipitare il proprio Paese in trappole di questo tipo.

Ecco spiegato perché, ancora oggi, i “presunti amici e fiancheggiatori” di Mario Draghi sono in realtà i suoi peggiori nemici. Che alimentano l’odio da tastiera, ma alimentano soprattutto gli argomenti dell’opposizione politica interna ed internazionale.

Non c’è motivo di scandalo, se si parla di manovre di palazzo e di manovre internazionali: il Mondo funziona in questo modo.

Nello specifico di Draghi, anche il suo arrivo a Capo del Governo italiano fu chiaramente il risultato di una manovra che vide coinvolti sia i partiti politici sia il mondo dell’economia. Anche questo, accade in Italia, in Europa, negli Stati Uniti. Nulla di cui scandalizzarsi, nulla di cui indignarsi.

Ciò che invece suscitava e suscita indignazione, allora ed oggi, è il tono elogiativo, spesso trionfalistico, adottato dai mezzi di comunicazione italiani nei confronti di Mario Draghi: quel tono che, come dicevamo più in alto, oggi rende ancora più aspro l’astio nei confronti della persona, e ne mina anche la solidità e la credibilità come Capo del Governo.

Difficile dire in che misura le sciocchezze che siamo stati costretti a leggere sui quotidiani, e ad ascoltare al TG5, al TG1, al TG7, sciocchezze che (del tutto a campione) vi ricordiamo con due immagini (qui sopra e qui sotto) siano state “approvate”, o quanto meno “assecondate” dal Presidente del Consiglio, o meglio dal suo staff addetto alla comunicazione. Nostro parere: avrebbe dovuto cercare di limitare, se non evitare del tutto, queste forme di “culto della persona”.

Ciò che rimane, a distanza di pochi mesi, è che questo tipo di celebrazioni personali fanno sorridere, in qualche caso anche ridere, e risultano piuttosto grossolane.

I titoli trionfalistici, a volte a tutta prima pagina, generano aspettative molto elevate nel pubblico: questi titoli dei quotidiani giustificano un rilassamento nell’opinione pubblica, che si sente autorizzata (dalla lettura dei quotidiani stessi) a credere che “tutto è risolto”, o meglio che “tutto è stato risolto da Mario Draghi”.

La pagina che vedete qui sotto, in particolare, a noi fa ancora, e sempre, ridere di gusto.

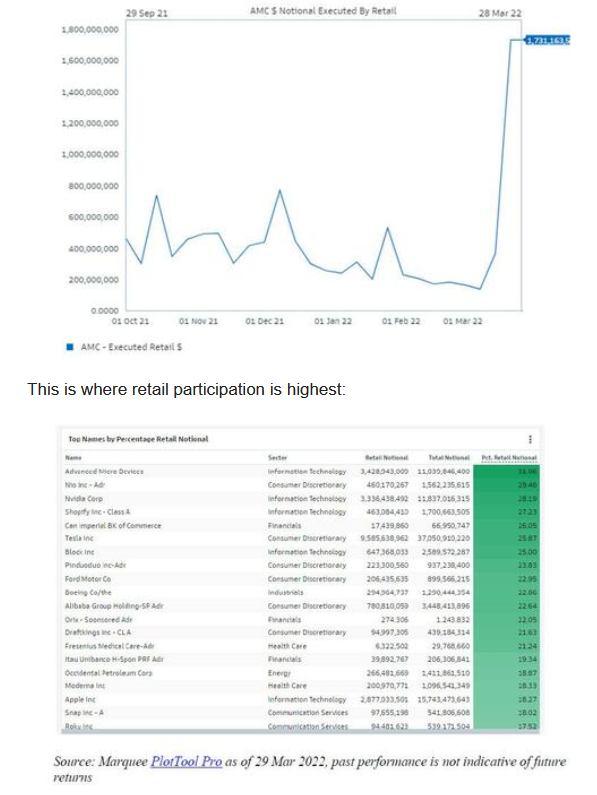

Lo stesso discorso vale per i mercati finanziari, ma soprattutto per gli investitori: indotti a scelte azzardate, e ad oggi sbagliate, da quei media che amano espressioni come “la Borsa vola” (nell’immagine qui sotto), decisamente più adatte alla pubblicità in Tv degli elettrodomestici.

Gli errori e le perdite degli investitori, però, meritano un approfondimento finale: da mesi noi ci chiediamo a che cosa stavano pensando quegli investitori che avevano in portafoglio i BTp nove mesi fa, quando il decennale del BTp a scadenza rendeva lo 0,50%.

Erano tutti convinti che sarebbe andata avanti così per sempre? Erano davvero convinti che “gli asini possono volare”? Possibile essere così tanto ingenui? E’ davvero credibile che decine di migliaia di investitori adulti e razionali abbiamo scelto di credere alle favole?

Possibile che, leggendo un titolo come quello che segue qui sotto, tutti gli investitori che avevano allo BTP in portafoglio a rendimenti vicini a zero abbiamo pensato: “Va tutto bene così, è normale, siamo a posto”?

Nel titolo c’è scritto: “la soluzione è: facciamo ancora più debito!”

E’ credibile che una persona razionale e di buon senso, dotata di un intelletto normale, leggendo un titolo come quello che trovate qui sopra e anche quello che segue qui sotto, non si sia fatto qualche domanda sui BTp fino al mese di maggio 2022?

Nel titolo che segue, potete leggere tutti: “stop austerità, più debito e meno paletti dall’Europa”. Parole semplici, comprensibili, non facili da equivocare: parole dirette, del tipo “facciamo un po’ quello che ci pare a noi”.

Volete dire che c’è qualcuno che non ha capito, neppure così? A noi sembra incredibile.

Ciò che vogliamo dire ai lettori, in questo Post, è che anziché insultare Mario Draghi sui social, la gran parte degli investitori italiani dovrebbe … insultare sé stessa.

“Siamo stati un po’ distratti, ed un po’ fessi: stava tutto scritto sul giornale, e in modo molto chiari, anche con dei titoloni".

Per poi concludere: “La prossima volta, faremo più attenzione. Oppure, ci affideremo a qualcuno capace, che ci metta in guardia dai pericoli.”

Parliamone, se volete.