Chi sia Mohamed El Erian i nostri lettori lo sanno da un decennio, e altri lettori lo hanno scoperto più di recente, quando lo hanno ritrovato in prima pagina sul Corriere della Sera (nel 2019, come abbiamo raccontato qui nel Post.

Noi utilizzeremo alcuni brani di una sua intervista della scorsa settimana per offrire ai lettori del Blog una anticipazione dei temi che ritroveremo nel 2020 come determinanti per la performance dei nostri portafogli.

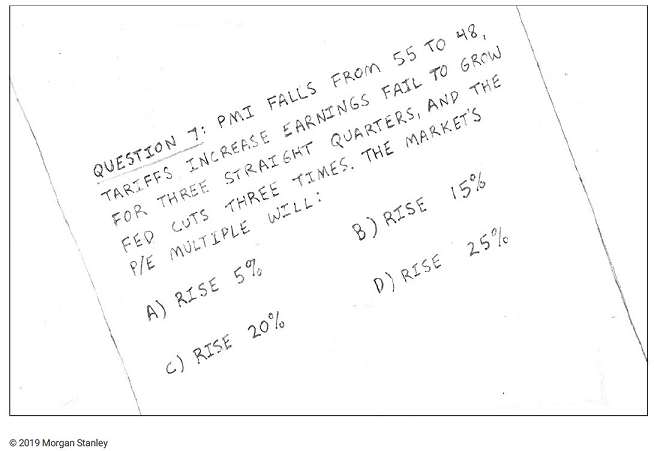

In questo quinto ed ultimo Post, arriviamo alle conclusioni. La chiave di lettura del 2019 è, a nostro parere e non soltanto a nostro parere, che si è trattato di un anno anomalo: anzi, di un anno abnorme. Nel 2019 abbiamo visto, come viene spiegato in modo efficace da El Erian, tre cose che sono impossibili da vedere allo stesso momento. Per questo, è giustificato affermare che i mercati nel 2019 hanno “inseguito un sogno”.

E questa avviamente non è soltanto una considerazione sul passato: è al tempo stesso una fortissima indicazione operativa per il futuro, e per i nostri portafogli in titoli.

Nevertheless, 2019 turned out to be one of the best years ever for investing. What kind of performance can we expect in 2020?

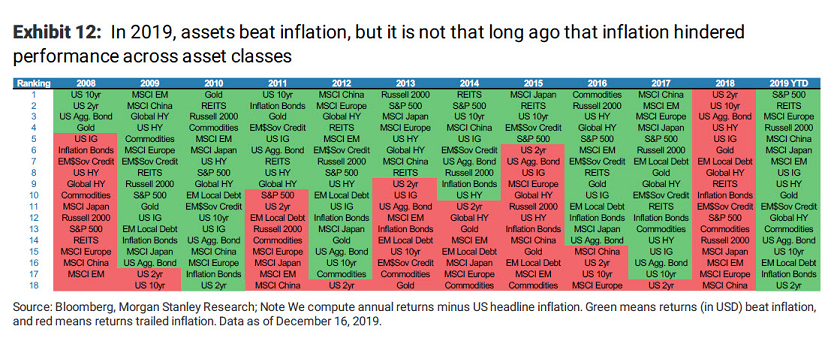

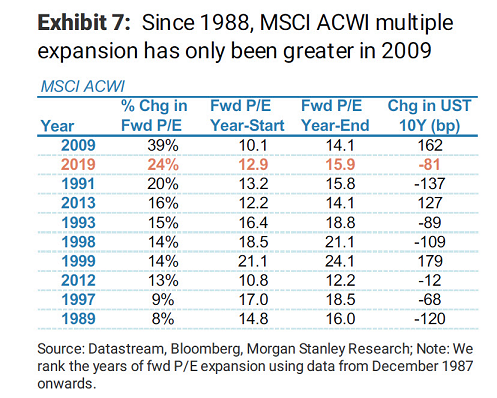

I’ve been calling it «livin' the dream» because we’ve had three things that are almost impossible to get together: One, you’ve had almost a 30% increase in US stock market indices. Two, on the whole, volatility was very low. And three, you’ve also made money on your risk-free assets. So the correlations have broken down, everything has worked for investors. The reason is liquidity: The relaxation of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and the ECB boosts all asset prices. They’re buying the risk-free assets which pushes investors to buy the risky assets, so everything goes up.

How long can this «dream» go on?

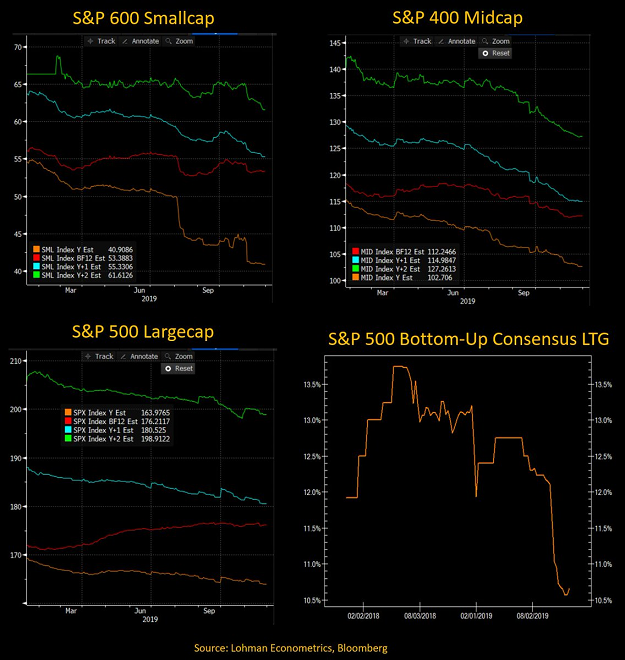

Going forward three or four years, this cannot continue. So this is a very good time to go up in quality: favor strong balance sheets and reduce exposure to illiquid asset classes that could get disrupted, like certain segments of the high yield market and emerging markets corporates. For example, two years ago, Argentina issued a hundred-year bond at 7,9% which was massively oversubscribed. Then, suddenly Argentina went into troubles and that bond came down quickly to trading at 30 Cents on the Dollar because no one is making the market as the price goes down. That’s because there are two types of investors in these assets: The dedicated investor who understands how these markets function, and «tourist investors» who come in because they’re attracted by the higher yield. The latter don’t understand the higher yield very well but it’s much better than what they get elsewhere. So when a problem occurs, they want to get out at any cost - and that’s why you get this massive gap in prices.

What should a prudent investor do in this kind of market environment?

If you’re like me and expect volatility, you want to have some cash to pick up good opportunities at cheap prices. So as you get rallies, you sell companies with weaker fundamentals and you do two things: You allocate some of that money to attractive opportunities and you build up your cash. People forget that cash performs multiple functions in a portfolio: First, it performs as a risk mitigation. Especially when yields are so low, it’s important to have cash as a risk mitigator. Second, cash gives you agility. The fourth quarter of 2018 was the perfect example. You could have picked up the big technology firms like Microsoft at very cheap prices. These firms are attractive when they sell-off big because they have very solid balance sheets, they are massive cash generators and they’re in a growing business.

Where else would you watch out for opportunities?

Markets overshoot on the way up and on the way down. That means sell-offs offer opportunities to take advantage of distressed situations trading at bargain prices. For instance, as much as Argentina is distressed, when that Argentine bond was trading at 30 Cents, the market had overshot. Here’s another example: There are Turkish multinational companies with assets outside of Turkey that are very reliant on Turkish banks. Since Turkish banks are lending less, you can lend to these companies with collateral outside of Turkey at double digit interest rates. And then, there is the issue of getting closer to the real economy: We are seeing more and more people co-investing in direct lending vehicles where you can find value as well. So it’s all about slowly re-orienting your portfolio because very short-term I’m constructive.