E' ancora peggio del Bitcoin? (parte 2)

La stampa quotidiana, in Italia, ha messo in prima pagina le dichiarazioni di Warren Buffett sui Bitcoin: guardandosi bene, però, dall'avvertire i lettori che forse nelle loro tasche oggi ci sta qualche cosa che è ancora più pericoloso.

Recce'd al contrario lo ha già fatto più volte, e ieri nel primo dei Post di questa serie. Nessun altro. E quindi nessuno in Italia è informato del fatto che la BCE è stata costretta a vendere di gran carriera alcune delle obbligazioni di tipo high yield che aveva acquistato solo due anni prima.

Per quale ragione? La Società emittente è stata accusata di falsificazioni nella contabilità. Ed il suo debito è stato downgradato a junk (spazzatura).

Il punto dove sta? perché il fatto interessa noi gli investitori finali? Leggiamo insieme: il testo è in inglese, ma vale la pena di fare un poco di fatica. Voi, ad esempio vi rendete conto di quanti di questi titoli ci sono nei vostri Fondi di Investimento? Sapreste dire che senso hanno, oggi, i prezzi in questa categoria di obbligazioni? sapere se e quando potrebbe presentarsi un "event risk" in questo comparto?

“We think it ought to make investors a little more cautious regarding cuspy eligible names,” Joseph Faith, a credit strategist at Citigroup Inc. in London, wrote in a Jan. 9 note. “In a world where almost all eligible bonds are priced to perfection, the Steinhoff sale has steepened the cliff between ‘in’ and ‘out’.”

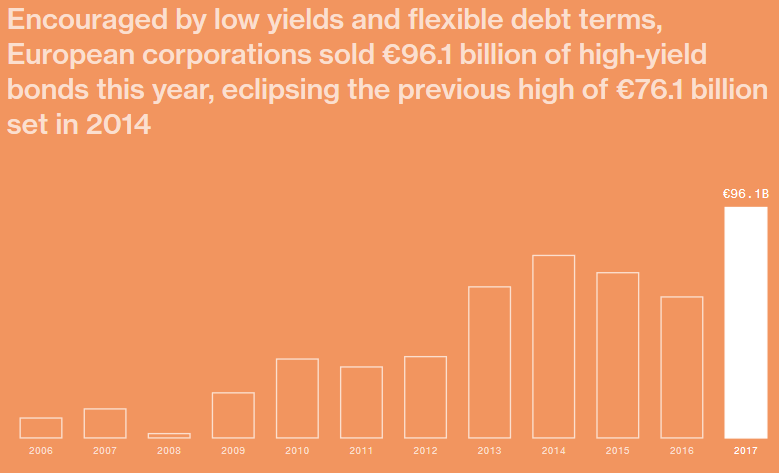

ECB purchases have boosted corporate credit across all ratings, eligible or not, since they were announced in March 2016, helping fuel a record year in European junk bond sales in 2017. While some expect the program to swell to more than 200 billion euros by the summer, this year looks set to mark a turning point for markets as central bankers pull back more on quantitative easing.

“If we’d hoped that in 2018 we could return to analyzing credit rather than CSPP eligibility criteria, the attention generated by the ECB’s unloading of Steinhoff shows that that day is still some way off,” Citigroup’s Faith wrote.

“While the sale crystallizes losses for the ECB, it also removes a source of ongoing controversy,” CreditSights analysts Tomas Hirst and David Watts wrote in a Jan. 10 note. Total acquisitions under the ECB’s asset purchase programs will halve to 30 billion euros a month from the start of this year and CreditSights said it assumes that CSPP portfolio purchases will be reduced pro rata.

The Steinhoff notes were the eighth to exit the central bank’s CSPP holdings after becoming ineligible for the program, following Arkema SA, Proximus SADP and Glencore Plc, according to data compiled by CreditSights.

Many remain sanguine about the central bank’s program and prospects for the credit market in 2018. If recent fund data showing inflows into credit continues, "then the high-grade market will simply not be able to create enough bonds to satiate the weight of demand and ECB buying," analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research wrote in a Jan. 10 note.

Absent a recession, the end of “happy days in credit” would require “an outbreak of hawkish and much less predictable central banks to end the great reach for yield,” according to the Bank of America analysts.

Still, they do flag another risk, a repeat of November 2017’s sudden rout in high-yield bonds.

“In bubblish times, investor confidence can quickly evaporate as event risks spook the market. If the smaller, debut, issuers -- where fundamentals are getting weaker -- become less scrutinized by the market, then this could mean more event risk shocks.”