“Tin foil hat”.

L’espressione è utilizzata dagli anglosassoni, ed in particolare negli Stati Uniti, per definire una particolare categoria di persone con disturbi mentali.

Potremmo definirli, in modo un po’ grezzo, i “matti inoffensivi”.

Il “cappello di carta stagnola” di cui si parla è quello che servirebbe a proteggere il proprio cervello dall’essere influenzato e controllato da onde di sconosciuta natura in arrivo dall’esterno.

In questo post, Recce’d sicuramente si occuperà di “matti”, ovvero persone che soffrono di gravi disturbi mentali. Se poi le persone di cui scriviamo nel Post siano “inoffensive”, beh … questo giudicatelo voi.

Se Recce’d dovesse scegliere una sola immagine, con la quale commentare e riassumere tutto il 2021 dei mercati finanziari, sceglierebbe l’immagine che qui sopra accompagna il titolo di Bloomberg

Il titolo dice che tra gli investitori americani si è diffuso un nuovo stile di investimento. E lo battezza (Bloomberg) come stile paranoico.

Il sottotitolo poi aggiunge: “Nel 2021, profeti della finanza e casse di risonanza su Internet hanno preso il predominio sui mercati delle azioni e delle criptovalute, hanno gonfiato la bolla finanziaria, ed hanno aperto la nuova era dello “identity investing”.

In linea teorica, noi potremmo anche chiudere qui il nostro Post: quale sintesi potrebbe essere più efficace?

E tuttavia, abbiamo deciso di proseguire: la ragione? Presto spiegata: ci è venuto un dubbio.

Abbiamo dubitato, e più di una volta nel 2021, che il malessere mentale che Bloomberg ha messo in prima pagina non sia limitato ai soli Stati Uniti. Sicuramente, negli Stati Uniti è più concentrato e più visibile.

Sicuramente, nessun mercato al Mondo è così gonfio ed inflazionato come quello degli Stati Uniti. Il fenomeno dei “cappelli di stagnola” (tin foil hats) è concentrato negli USA: non ci sono dubbi.

Ma anche qui da noi, in Italia, abbiamo registrato qualche segnale che disturba: atteggiamenti del tipo “non ho ancora guadagnato abbastanza”, “si sarebbe potuto guadagnare di più” e così via.

La confusione tra “investire” e “guadagnare” è grandissima: si investe solo se e quando si è consapevoli di poter perdere denaro, solo se si prende da subito in considerazione il fatto che è necessario gestire delle minusvalenze, e soprattutto quando si è consapevoli che proprio dal fatto che si potrebbe perdere denaro deriva il fatto che dopo, e solo per alcuni, ci sarà una ricompensa, un rendimento, una performance.

Se al contrario si diffondono atteggiamenti che con l’attività di investimento hanno nulla a che fare, e che guardano soltanto il lato del guadagno, allora tutti noi sappiamo di essere in una nuova fase dei “cappelli di stagnola”. Proprio quello dell’immagine più sopra, quel cappello, e quel soggetto che c’è sotto.

Per questo ci siamo detto: questo è stato il tema più importante del 2021, per tutti gli investitori del Mondo, e lo sarà anche nel 2022, ma in modo del tutto diverso dal 2021.

Nel 2022 ci saranno quelle che si definiscono le “inevitabili conseguenze”.

Per questa ragione è utile, ai nostri lettori, approfondire. Vi invitiamo a farlo leggendo il qualificatissimo articolo che segue, e che Recce’d ha scelto per voi.

Il succo di questo bellissimo articolo, però, lo trovate nelle ultime righe: ragione per cui, se proprio avete fretta …

… ma è un peccato, se non leggete quello che viene scritto prima.

“Every age has its peculiar folly; some scheme, project, or phantasy into which it plunges, spurred on either by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the mere force of imitation.

Failing in these, it has some madness, to which it is goaded by political or religious causes, or both combined.”

--“Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds,” Charles Mackay

“When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”

-- “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” Hunter Thompson

The year 2021 will be remembered as one in which markets tumbled down a rabbit hole and entered financial wonderland: A once-elite undertaking became more populist, tribal, anarchic and often downright bizarre.

Retail investors upstaged hedge funds, crypto squared up against fiat currencies and financial flows crushed fundamentals. Farewell stocks, hello “stonks”: Memes matter now.

Here’s a taste of the madness: Entrepreneur and social media puppet master Elon Musk became the world’s wealthiest person. Tesla Inc.’s market capitalization exceeded $1.2 trillion, more than the next nine largest automakers combined.

One of those others, Rivian Automotive Inc., went public in November and only recently started generating revenue. It was soon valued at $150 billion.

Hundreds of special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs, together raised more than $150 billion to find a company to list on the stock exchange, with their targets often more of a business plan than a business.

SPAC Attack

Cryptocurrencies, the bulk of which have no intrinsic value, were at one point collectively worth more than $3 trillion. A non-fungible token artwork (NFT) — in this case, a JPG file by an artist named Beeple — sold at a Christie’s auction for $69 million.

Struggling video games retailer GameStop Corp. and cinema chain AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. soared as much as 2,450% and 3,300%, respectively, when Redditors coordinated online to punish hedge funds that were betting on the companies’ demise. 1

And because there’s no gold rush without pickaxes, retail brokerage Robinhood Markets Inc. and crypto exchange Coinbase Global Inc. became two of the year’s biggest initial public offerings: At the peak they were valued at $59 billion and $75 billion. (In December the home of WallStreetBets, Reddit Inc, announced it had filed confidentially for an IPO)

Monthly active users measures how many customers interact with Robinhood services during a given month. It does not measure the frequency or duration of those interactions.

Investors have poured an astonishing $1 trillion of cash into equities funds in the past 12 months, or more than the combined inflows of the past 19 years. At the peak in January, retail investors accounted for almost one quarter of U.S. equities trading, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

An estimated 16% of U.S. adults have invested in crypto, according to Pew Research Center; among twenty-something men, that proportion is closer to half. In 1929 shoeshine boys gave out stock tips; today’s teenagers ask their parents to open a crypto trading account on their behalf.

Crypto Demographics

The short explanation for all this feverish activity is that thanks to central bank and government stimulus, far too much money is sloshing around in the financial system. The aggregate money supply has increased by $21 trillion since the start of 2020 in the U.S., China, euro zone, Japan and eight other developed economies. “Stocks only go up” isn’t just a wry catchphrase: Essentially it’s been the lived experience of young investors this past decade. And so they ignore nosebleed valuations and buy the dip.

But something’s changed too in the culture of investing. It’s no longer enough to admire a company or asset and buy the stock or token. Some of the biggest investing trends have become an extension of personal identity, akin to your religion or your sports team. Sometimes that connection is overt: From Christmas Day the home of the L.A. Lakers will be renamed the Crypto.com Arena. Footballer Tom Brady has launched his own NFT collection.

These movements can be fun and empowering, but financial super-fandom can quickly become toxic. I worry that the same forces diminishing modern politics — partisan divisions, pervasive distrust, social media echo chambers, misinformation, cancel culture and conspiracy theories — are seeping into the investing world, where they’re warping capital allocation, inflating a series of bubbles and challenging the ability of regulators to protect investors and the markets.

In some respects, this time really is different. Easy to use, commission-free brokerage apps like Robinhood have given millions of neophytes the tools to play at being a Wall Street trader.

Instead of sticking their money in a boring index fund, young investors are making concentrated bets on single stocks and using cheap short-dated out-of-the money call options (speculating the price of the stock will quickly increase before the option expires). It’s the financial equivalent of buying lottery tickets.

Options Mania

Shows small trader call buys to open minus put buys to open as % of NYSE share volume. Small trades defined as ten contracts or fewer, which is mostly retail order flow.

It can be an effective way to squeeze the underlying shares higher (because option sellers hedge their position by buying the stock). It often attracts momentum-buying from hedge funds and other institutional investors, which magnify the price moves. And options are also a huge money-spinner for digital brokerages. Problem is, inexperienced retail investors may not fully understand the risks, until it’s too late.

“It’s much more like gambling,” says Bloomberg Intelligence market structure analyst Larry Tabb. “The options premiums might seem pretty small but you can easily end up losing your entire investment.”

Speculative assets have evolved, too. In 2000 investors could easily comprehend the business model of a Pets.com, say. There’s now a much higher degree of financial abstraction: Think SPACs, NFTs, Web3, DeFi ( “decentralized finance”) and the metaverse. This abstraction excites intellectual curiosity but the harder something is to explain, the easier it is for promoters to hype it to people lacking a financial or technical background.

Fearing they’ll be accused of stifling innovation or capital formation, regulators have mostly allowed the party to continue. Digital assets typically aren’t registered and regulated as financial securities. Crypto trading often happens on opaque, offshore exchanges. SPACs can publish fantastically optimistic financial projections, which traditional IPOs avoid due to liability risks. It smacks of regulatory arbitrage on a grand scale.

Another important check on speculative excess, the short-sellers who think a stock is overvalued, had a difficult year. That’s not to say they didn’t enjoy some successes — former SPACs have been particular fertile ground for the shorts — but the market’s relentless rise and the danger of being caught up in a GameStop-like squeeze convinced some to give up the game entirely. To cap it all, much to the delight of the Reddit crowd, short-sellers now face a U.S. Justice Department criminal investigation into their activities.

The GameStop saga and similar events also torpedoed a key theoretical foundation of Wall Street — the notion that markets are efficient. Securities prices are supposed to reflect all known information and the discounted value of expected future cash flows. If prices rise more than is justified by financial fundamentals, more sophisticated investors should sell.

Defying Gravity

An emerging theory, the Inelastic Markets Hypothesis, postulates that retail buying is able to warp prices for prolonged periods because so much of the market is now passive, not actively managed, and is therefore insensitive to changes in prices.

“Demand shocks and inelastic markets are the tissue that connects the meme stocks, Tesla and even crypto” says Philippe van der Beck, a researcher at the Swiss Finance Institute. 2 “Bitcoin can be seen as an extreme version of today’s stock market: it’s almost entirely detached from fundamental value as there are no cash flows for investors to discount. People are just betting on how they think demand for the asset will change in the future”

When flows trump fundamentals and financial prophets, not accounting profits, drive investment decisions, attention becomes the only trading currency that matters.

True, retail investors are a heterogenous bunch, and include green eyeshade value investors who pore over spreadsheets. But increasingly, the hallmarks of the retail investing world have been dizzy-eyed techno-optimism, tear-it all-down nihilism and cult-like fanaticism.

This transition shouldn’t come as a surprise. Not only have markets been roiled by the same events and forces that stoked fear, division, turmoil and mistrust in society at large, but the 2008 financial crisis set back a generation’s earnings prospects and engrained a feeling that Wall Street always wins. Politics appears irredeemably broken, mainstream media is no longer trusted, and technology upstarts that once promised a better and more equitable world have become impregnable behemoths.

And that was before Covid hit.

Young people are starting careers with massive student debts and housing has again become crazy expensive: It’s no wonder they dumped their stimulus checks into the stock market and gamble to keep up. The FOMO is real.

Those who now proclaim a new financial dawn find a receptive audience. Hence the excitement around decentralized finance (who needs bankers?!), and the collective elation during the GameStop phenomenon: Ordinary investors suddenly feel incredibly powerful. “Professional investors would never have paid attention to Reddit boards two to three years ago,” says Tabb. Now they do.

Of course it’s hard to fully rationalize buying a joke dog token or one named after a coronavirus variant — but you only live once (YOLO). And as long as the prices go up, who cares why?

Memes and in-group language foster a feeling of togetherness that people have missed during an insolating pandemic.

Online forums like r/wallstreetbets help day traders to share sophisticated ideas, champion the little guy (it’s often men) and humorously commiserate about spectacular losses.

Users of YouTube, TikTok, Discord, StockTwits and Twitter also push out a wealth of financial information that theoretically enables better investment decisions.

But there’s a catch. The retail investor commandment to “do your own research” sounds responsible, but financial influencers often hold positions in the assets they’re touting. A lot of digital financial content is little more than shilling.

Retail investors can also end up in digital echo chambers and fall prey to confirmation bias. “It can affect the information you see. A Tesla bull may only see positive news about the company whereas on the same day a Tesla bear’s news feed will tend to have much more negative news in it,” says Tony Cookson, an associate professor of finance at the Leeds School of Business, University of Colorado, who has researched this phenomenon. “It’s financially costly to selectively read things that reinforce your existing views.”

Moreover, some of the year’s defining financial obsessions pretend to be egalitarian and freewheeling but at their core are highly dogmatic. Don’t just take my word for it. “These days even the most modest critique of cryptocurrency will draw smears from the powerful figures in control of the industry and the ire of retail investors who they’ve sold the false promise of one day being a fellow billionaire. Good-faith debate is near impossible,” the co-creator of Dogecoin, Jackson Palmer complained in July. (Dogecoin is a joke cryptocurrency that became a $23 billion meme sensation when Musk touted it to his followers.) Palmer wasn’t done:

The cryptocurrency industry leverages a network of shady business connections, bought influencers and pay-for-play media outlets to perpetuate a cult-like “get rich quick” funnel designed to extract new money from the financially desperate and naive.

— Jackson Palmer (@ummjackson) July 14, 2021

True believers seek to reinforce these financial echo chambers, by attacking even mild “fear, uncertainty and doubt” (FUD). And rather than engage with them, they often block out or cancel critics.

There are guides on how to troll “no-coiner” journalists like me — “have fun staying poor!” is a common refrain — and they emphasize the importance of getting information only from like-minded crypto people.

In this climate, scams and misinformation proliferate. New coins are pumped and then dumped by their creators. Retail investors are encouraged to HODL (never sell) and have “diamond hands,” even though if the price collapses they’ll be left holding the bag. “It’s typical of mania environments that the crowd is no longer capable of distinguishing the predators,” says Peter Atwater, president at Financial Insyghts LLC and an expert in social psychology.

A common enemy, real or imagined, disciplines the herd so investors don’t get bored and take their money elsewhere.

Bitcoin “maximalists” argue all other coins are inferior: In their laser-eyed view of things, central bank money-printing will end in ruin and Bitcoin is destined to become a new global reserve currency.

Digital Gold?

Goldbugs have been obsessed with sound money for decades, but their philosophy has now been more effectively weaponized. With crypto “we’ve decided to do the most American thing ever, to commoditize our rage at the financial system into a financial product,” writes the software engineer and crypto critic Stephen Diehl.

After raging against hedge funds that shorted GameStop, the “apes” shifted their ire to discount brokerage Robinhood Markets Inc, claiming it conspired with market-maker Citadel Securities to restrict their trading. “There are those who still refuse to believe an American landed on the moon,” Citadel tweeted in September lambasting “internet conspiracies and Twitter mobs” for ignoring the facts.

Similarly, hardcore AMC shareholders are obsessed with the idea that the mother of all short-squeezes (MOASS) will propel the stock to new, incredible heights. The stock has fallen more 50% since the June peak. Salvation must wait.

Waiting for MOASS

No wonder it’s hard for members of the financial elite to come across as authentic to retail investors — witness this cringe-inducing endorsement of Crypto.com by the actor Matt Damon.

Attracting ordinary investors can also backfire, as billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman discovered this year when his $4 billion SPAC, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings Ltd., announced and then abandoned buying a stake in Universal Music, much to Reddit’s chagrin.

But that hasn’t stopped establishment figures from trying to co-opt the retail wave for their own purposes: After all, the rewards can be huge.

Nobody has pulled this off better than the crypto-touting, master of memes Elon Musk. “If you drew a Venn diagram of every major financial theme in the past decade then you’d find Musk in the middle,” says Atwater. “Normally you can’t be folk hero and the richest person in the world, but he’s done a masterful job of selling people the dream they wanted to buy, at least for now.” And Musk seems very aware of his power.

thinking of quitting my jobs & becoming an influencer full-time wdyt

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) December 10, 2021

AMC boss Adam Aron embraced the “apes” and saved his company by selling more stock. Since then the cinema chain has jumped on seemingly every populist investing trend, from accepting meme coin Shiba Inu (SHIB) as payment to issuing NFTs.

Cathie Wood’s futuristic pronouncements made her a star on social media and sucked more cash into her risky Ark Investment Management strategies.

And former Facebook executive Chamath Palihapitiya parlayed anti-establishment rhetoric into a portfolio of SPACs — the “poor man’s” private equity, with as many egregious fees.

Politicians are catching on too. Donald Trump’s digital media venture struck a SPAC deal that seeks to harness the same tribalism he nurtured and exploited as president. So far, the price has risen five-fold. El Salvador’s “millennial authoritarian” president Nayib Bukele was embraced by the crypto crowd after he declared Bitcoin legal tender. When crypto prices crashed in early December, the head of state informed his social media followers that El Salvador was buying the dip...

As we neared the end of 2021, crypto, unprofitable tech and the meme stocks have all sold off, hurting retail portfolios. With persistent inflation bringing forward expectations of interest rate hikes, Wood’s Ark funds and Palihapitiya’s SPAC bets were among those caught in the downdraft.

Lifeboat Needed?

These bubbles may not have burst for good; retail investors may just have shifted their attention once more. They began feverishly buying Apple Inc. call options, for example, helping to push the iPhone maker’s valuation toward a mind-boggling $3 trillion. Shares of new Reddit favorite Ford Motor Co. have lately outperformed Tesla.

Speculative excesses aren’t all bad: Some of the cash that’s poured into markets into 2021 will fuel real innovation — Musk’s technological achievements are impressive.

However, the longer manias persist, the more capital is misallocated and the greater the risks for financial stability. The implosion this year of property giant China Evergrande Group, family office Archegos Capital Management and U.K. fintech Greensill Capital revealed fragilities that ever-rising markets conceal, as well as the dangers lurking in leverage, derivatives and concentrated exposures. Moreover, today’s most speculative assets are often interconnected — people who own Tesla also own Bitcoin; indeed Tesla owns Bitcoin! 3 — amplifying potential volatility.

So I’m glad Gary Gensler, the new head of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, has outlined an ambitious policy agenda, spanning the “gamification” features of trading apps, SPAC financial disclosures and “Wild West” crypto markets, including lending and so-called stable-coins (the most important of these, Tether, is supposedly fully backed by dollar financial reserves but not everyone’s convinced).

Here’s my non-virtual two cents: I think we need greater oversight of crypto trading platforms and more digital assets should be regulated as financial securities. And I’m in favor of tightening access to options trading to prevent inexperienced investors losing their shirts.

But let’s face it: Regulators can’t turn back the clock. It’s not their job to heal societal divisions and they can’t police everything investors do and say on the internet. Democratized finance is here to stay. We must learn to live with it.

In a world of social media hype and increasing financial abstraction, teaching basic financial literacy and how to find unbiased investing advice will be vitally important.

Sadly, I fear the current generation of young investors may have to learn the hard way. Eventually people will tire of phony financial prophets and pump-and-dump markets. And then, as everyone makes for the exit, of the losses that pile up in their Robinhood accounts.

L’articolo che avete appena letto (ci auguriamo che lo abbiate letto tutto) restituisce in modo efficace il clima che tutti hanno respirato, sui mercati finanziari, nel 2021.

C’è chi ha abboccato a queste esche, c’è chi ha esitato lasciandosi influenzare emotivamente, c’è chi ha resistito al richiamo di questi lustrini accattivanti.

La ragione, chi ce l’ha?

Ce lo dirà il 2022.

Nel mondo degli investimenti, i guadagni sono quelli che si misurano nella realtà, e non sulla carta.

Quando la fase di mercato dei “cappelli di stagnola”, a tutto oggi estremamente fragile (lo avete visto tutti nel dicembre 2021) si sarà completata, allora (e solo allora) si tireranno le somme.

Solo alla fine, quando sui quotidiani e ai TG si scriverà e si parlerà di una avvenuta “normalizzazione”, potremo dire con fondate ragione, chi ha avuto torto, chi ha saputo gestire gli investimento e chi invece si è soltanto molto agitato ed emozionato per qualche cosa che non è mai esistito.

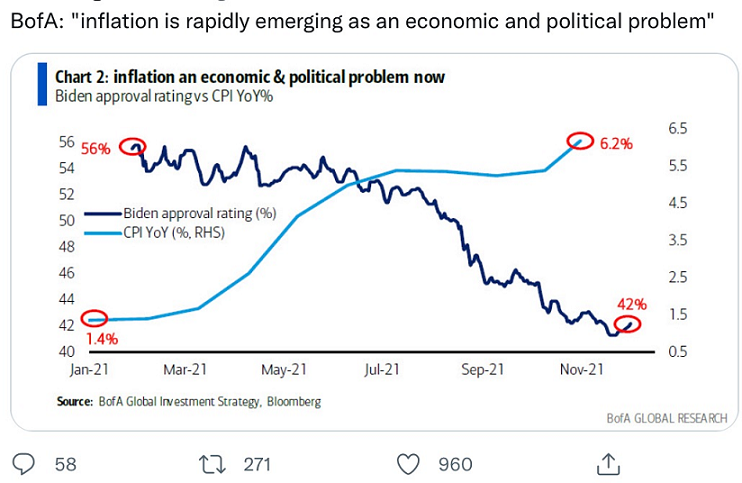

La stessa cosa, ad esempio, la avete vista tutti con l’inflazione 2021: nel mese di aprile, tutti avevano ragione, sia chi sosteneva che a dicembre l’inflazione sarebbe scesa di nuovo al 2,5% negli Stati Uniti (ed a zero da noi) sia chi sosteneva che sarebbe salita ancora, magari al 7%.

Tra i due soggetto, però uno solo aveva ragione: l’altro, si sbagliava.

Ed è così, e sarà sempre così, anche nel mondo degli investimenti.

La linea di Recce’d, e la strategia che ne deriva per la gestione dei portafogli modello, è molto chiara e ben nota ai nostri lettori ed amici, e sicuramente non la abbiamo modificata per rincorrere quelli “con il cappellino di stagnola”.

Ci mancherebbe altro.

Il ruolo di ogni gestore di portafoglio che sia professionale e non spegiudicato, consapevole e non azzardato, orientato al rendimento e non alle scommesse di azzardo, in momento come questi è esattamente quello di pensare prima alla protezione dei patrimoni dei propri Clienti, e solo dopo all’inseguimento delle opportunità

E, lo ripetiamo ancora una volta, le opportunità di guadagno, quelle vere, partono dal COMPRENDERE la situazione 2021, e sfruttare le opportunità che ne DERIVANO.

Non fare la prima mossa: guadagnare con la SECONDA.

Di recente, ne ha scritto sul Financial Times persino lo strategista della divisione Fondi Comuni di Investimento (ovvero dei prodotti finanziari) di Morgan Stanley, la grande banca globale di investimento.

Persino loro, persino Morgan Stanley, uno dei player che hanno alimentato, nel modo più attivo, questa ondata di follia nel mondo degli investimenti, persino loro riconoscono (un po’ tardi, ma sempre meglio che niente ..) che il panorama del mondo degli investimenti nel 2021 è stato alterato, profondamente, dai comportamenti dei “cappelli di carta stagnola”.

Nell’articolo si parla degli investitori al dettaglio, e ricorre il termine “mania”: un termine che noi giudichiamo del tutto appropriato, per il 2021 dei mercati finanziari, e in questo ci sentiamo pienamente supportati dai dati che leggete qui sotto nell’immagine.

L’articolo di Morgan Stanley che segue è rilevante per molte ragioni: tra le tante, vi segnaliamo l’accenno, importantissimo (e già fatto anche da Recce’d in questo Blog) ai problemi di natura sociale e soprattutto politica che verranno generati proprio da questa situazione anomala, ai limiti della follia, dei mercati finanziari.

Leggendo l’articolo che segue, vi convincerete che mai come nel 2021 era opportuno adottare criteri e strategie di investimento diverse dal solito, e protettive, e sganciate dagli indici dei mercati finanziari.

Esattamente ciò che Recce’d ha fatto, per i propri Clienti.

Arguably, the bull market of 2021 is the same one that started in 2009, with one big change. Retail investors, who sat on the sidelines for so many years, rushed in after the pandemic-induced flash crash last year and have since been buying every dip with mounting enthusiasm.

They represent not only a new cohort of investors but a new voting bloc, increasing the risk of populist backlash should one of the dips turn into another bear market. Remember that policymakers played a big role in starting this craze. Flush with government support cheques and fresh liquidity from central banks, new investors began pouring part of their income into markets, helping to turbocharge the bull run into a 13th year. More than 15m Americans downloaded trading apps during the pandemic, and surveys show many of them are young, first-time buyers.

Retail investors have also been hyperactive in Europe, doubling their share of daily trading volume, and in emerging markets from India to the Philippines. All told, US investors alone poured more than $1tn into equities worldwide in 2021, three times the previous record and more than the prior 20 years combined. After retreating last decade, US households overtook corporations as the main contributors to net demand for equities in 2020. They now own 12 times more stock than hedge funds.

Media coverage tends to peak at the zaniest moments, such as when the Robinhood crowd was going gaga for GameStop and other meme stocks last winter, but the craze never slowed. Retail investor “interest”, measured by internet searches for popular market news and trading outlets, has continued to climb skyward. US households bought at an astonishing pace throughout 2021, peaking in the third quarter when their stock holdings rose by more than 16 per cent over the previous year. That level of new retail flows matches the prior record, set in 1963.

Alas, going back to the crash of 1929, one common feature of bull markets is that retail investors catch on too late. Today, they continue to buy even as corporate insiders are selling in record amounts, with insider sales topping $60bn this year. And insiders have the opposite record: they tend to sell at the peak. Should the market turn sharply, the fact that high-profile CEOs moved to reduce their risks in time will only serve to encourage outrage among smaller investors who did not. Instead of counselling caution, however, Democrats and Republicans, in a rare bipartisan show of unity, have cheered the “democratisation” of markets and defended the right of Americans to speculate freely on meme stocks — even if it seems irrational. Another warning sign of impending trouble for the markets is heavy borrowing to buy stocks, or margin debt.

Net margin debt in the US now amounts to 2 per cent of GDP, a high since records began three decades ago. A large chunk of it is on the tab of retail investors: their borrowing to buy stock rose by more than 50 per cent over the past year to record levels, much as it did before the crashes of 2001 and 2008. Democratisation of markets would be an unalloyed good, if the risks were managed sensibly. Big players never had a corner on “smart money”, and that may be more true now than ever, since internet technology has at least partly equalised access to market intelligence for investors of all sizes.

Retail investors are hardly the only ones showing signs of mania, which are also visible in the markets for IPOs, mergers and art. But many retail investors are placing their bets in a highly speculative way, for example by buying one-day call options or stocks with low nominal value that are easy to lever up. It is a surreal sign of confusing times to hear avowedly socialist political leaders defend extreme capitalist risk-taking by a class of investors that includes many lower and middle-income voters.

The result is a market that is historically overvalued, over-owned and to a perhaps unprecedented extent, politically flammable. Americans now have an unusually high level of savings and the share of their portfolios that they hold in stocks now matches the all-time high, going back to 1950. None of this necessarily portends an imminent crash. There is still plenty of liquidity sloshing around the system and even some of the most sophisticated investors fret that there is no alternative to owning stocks with interest rates so low. But having done so much to inspire this retail investor mania, governments and central banks could face a major backlash when the next bear market inevitably arrives.

The writer, Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s chief global strategist, is author of ‘The Ten Rules of Successful Nations

Come avete letto nell’articolo di Morgan Stanley, fin dalla grande Crisi del 1929, una caratteristica ricorrente dei grandi disastri finanziari è che “i piccoli investitori al dettaglio arrivano alla festa sempre troppo tardi”.

A questo proposito. Noi abbiamo segnalato, ai nostri Clienti, attraverso il bollettino quotidiano che si chiama The Morning Brief, che ci sono stati negli ultimi due mesi alcuni segnali che si potrebbero definire “strani”: rispetto a ciò che abbiamo visto nel recente passato, ci è sembrati di cogliere in alcune dichiarazioni di alcune Autorità (politici e banche centrali) una sfumatura molto diversa, a proposito dei mercati finanziari. Ci è sembrato di leggere, tra le righe, che una “piccola crisi finanziaria” toglierebbe molte … castagne dal fuoco.

Siamo certi che tutti quelli del “cappello di carta stagnola” a questo non hanno pensato. E sono in tanti, col cappellino.

Ci ha pensato, invece, il Wall Street Journal, pubblicando il testo del qualificato articolo che trovate che segue qui sotto, e che è stato pubblicato subito dopo la riunione di metà dicembre della Federal Reserve, la riunione della ulteriore “svolta ad U” della Banca Centrale più grande del Mondo, ormai del tutto in balia degli eventi.

L’articolo che segue, e che chiude il Longform’d di oggi, vi può essere utile anche come introduzione al tema delle “financial conditions”, un indicatore che risulterà la chiave delle vostre performances nel 2022: forse, quello più importante in assoluto.

Oggi noi non abbiamo tempo e spazio per approfondire, in questo post, ma sicuramente lo faremo in un prossimo Post.

Nel frattempo, ne scriveremo ogni mattina in The Morning Brief, per i nostri Clienti.

Vi lasciamo alla lettura per poi proporvi, più in basso dopo l’articolo, le nostre conclusioni sul tema di questo Post.

The Fed May Have to Kill the Stock Market’s Rally to Quash Inflation

By Randall W. Forsyth

Updated Dec. 16, 2021 7:56 am ET / Original Dec. 15, 2021 6:46 pm ET

Inflation will ease markedly while interest rates remain historically low and negative in real terms, even as the labor market returns to full employment, according to the latest economic projections from the Federal Reserve.

This would be the best of all economic possible worlds. Indeed, it is a forecast worthy of Dr. Pangloss from Voltaire’s Candide, who called this the best of all possible worlds—in contradiction to the reality around him.

In an apparent sigh of relief Wednesday, stocks reversed earlier losses following the widely anticipated announcement by the Federal Open Market Committee that it will taper its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage securities twice as quickly as previously indicated, by a total of $60 billion per month in January.

That, in turn, would set the stage for the initial liftoff in the federal-funds target rate, from the current rock-bottom 0%-0.25%, by the spring. According to the FOMC’s “dot plot” of forecasts of committee members, their median guess is for three quarter-percentage point increases by the end of 2022, with another three hikes in 2023 and two more by the end of 2024.

Conventional wisdom calls this a hawkish pivot, which it may be given that the Fed’s previous dots envisioned only a single quarter-point hike next year and maybe a couple more in 2023. But Fed Chairman Jerome Powell admitted inflation has proved anything but transitory (with the T word excised from the FOMC’s policy statement). And at his press conference, he acknowledged the labor market has made much faster progress toward the central bank’s goal of full employment than expected.

“Powell did his job to explain how the world has changed and how a lot of their forecasts were based on assumptions that have proved incorrect,” Julian Brigden, head of Macro Intelligence Partners, told Barron’s. “He’s now addressing inflation and a labor market that for all intents and purposes has healed.”

What the markets fail to grasp, however, is that a far greater tightening of financial conditions will be needed to bring about the descent in inflation envisioned in the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, Brigden added.

The Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditure deflator, is expected to be cut by more than half next year, to 2.6% from the current estimate of 5.3% for 2021. From there, the PCE deflator is expected to enter a glide path to 2.3% and 2.1% in 2023 and 2024, respectively, or virtually spot on with the Fed’s long-run target of 2.0%.

Unemployment is forecast to fall from 4.3% at the end of 2021 to 3.5% in the next three years. Powell wouldn’t be pinned down about what would constitute the Fed’s goal of maximum employment, which he said at his Wednesday press conference couldn’t be captured in a single number, as with inflation.

Brigden says for all intents and purposes, full employment has been met. Powell himself took note of key indicators consistent with full employment, including wage growth and the quits rate. And as Joseph Carson, former chief economist of AllianceBernstein, points out in his blog, after a steep fall in the jobless rate this year, there are 11 million job openings, four million more than there are unemployed.

What the stock market doesn’t realize is how much financial conditions have to tighten to tamp down inflation as the Fed forecasts, Brigden says.

Even with its latest pivot, monetary policy will remain accommodative. The Fed will still be expanding its balance sheet (thus adding liquidity), only more slowly. Hiking the fed-funds rate three times, to 0.75%-1%, by the end of 2022, would leave this key rate still sharply negative in real terms (that is, well below the rate of inflation), an easy policy by any criteria.

Other components of financial conditions include the dollar’s exchange rate, short-term Treasury rates, longer-term Treasury yields, corporate-credit risk spreads, and, last but not least, the equity market. A significant correction in stock prices would be consistent with the requisite tightening in financial conditions needed to slow inflation, Brigden concludes.

The stock market’s post-Fed rally was based on the pleasant notion that the central bank would be able to achieve its objectives of bringing inflation back into line along with full employment, all while continuing easy financial conditions. In other words, the best of all possible economic and financial worlds, as seen by Dr. Pangloss.

Le conclusioni di questo lavoro sono le seguenti: quando sul mercato prevalgono i matti (come dice anche il titolo di Bloomberg qui sopra) allora anche noi, tutti noi investitori, al dettaglio oppure professionali, ogni giorno ed ogni ora siamo costretti a ragionare come ragionano i matti.

Per poi fare, naturalmente, tutto l’opposto di ciò che fanno i matti. Ma a questo, ci siete già arrivati anche voi lettori: camminare sui cornicioni dei palazzi di trenta piani, come tutti sanno, non è salutare, non lo è nel breve, non lo è nel medio e anche nel lungo termine.

Di questo tratterà la nostra Lettera al Cliente che verrà spedita la settimana prossima, che è l’ultima del 2021 e che anticipa le prime scelte operative del 2022. Un anno che sarà per i nostri Clienti e per noi un grande anno, un anno decisivo nella storia di Recce’d.

L’anno della riconciliazione, come spiegheremo proprio nella Lettera al Cliente di fine anno.